CW: death; violence; trauma

The concept was simple. You sit a bunch of people in a circle– everyone who hurt, everyone who got hurt, all affected– and let them share. They talk about themselves, say about how they have changed, how their lives are after this thing that happened.

Some people, it helped them heal, for sure.

Others went in angry and left a different kind of angry. Learned how the blame belonged on the system, the history, the colonizer, the big things that were harder to change than one bad person.

Some people did good with it, got all radicalized, energized, went out and tried to change the world. Some were empowered like that, but those ones were usually already empowered.

Others though, they hurt. They kept hurting.

– Katherena Vermette, The Circle (2023, p. 59).

I am a former neighbour to the folks who live at 143 Langside Street, the site of one of the worst mass shootings in the history of so-called Winnipeg. For weeks, I have been grappling with this news; how could such violence occur to my neighbours, the folks I shared the back lane with, and lived right next to?

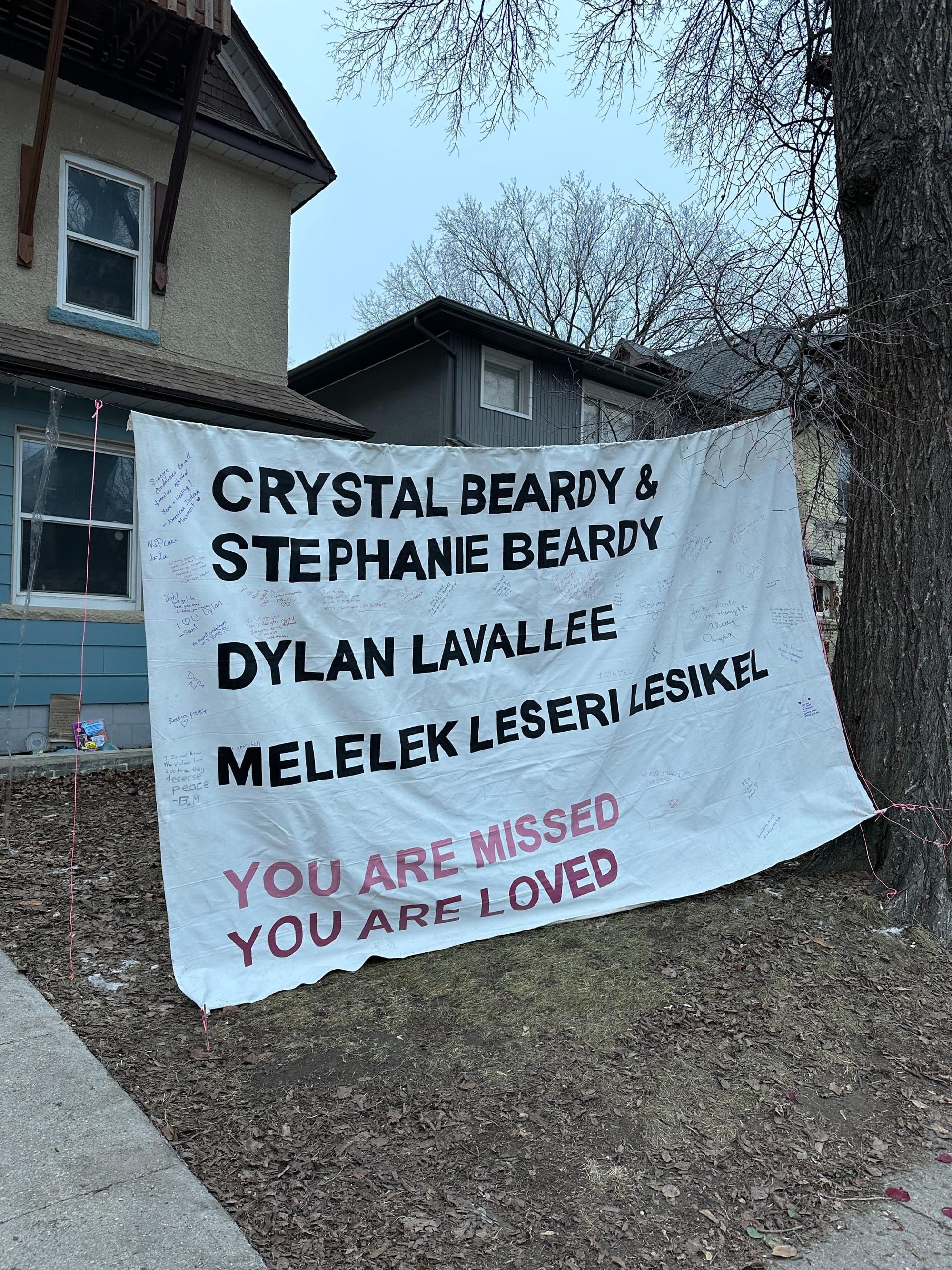

I mourn for Crystal Shannon Beardy, Stephanie Amanda Beardy, Melelek Leseri Lesikel, and Dylan Maxwell Lavallee. I mourn for the community. I also mourn for the person who allegedly killed them, Jamie Randy Felix.

This is a heartbreaking tragedy that weighs heavy on my spirit, has shaken the community, and is something that I have come to understand aptly encapsulates the many scales of intimate violence that the colonial state wages on people who live within their so-called borders.

Mass shootings don’t happen in healthy and well-supported communities. The atrocity on Langside lays bare not only the state’s grave failure to care for people writ large, but also how intersecting layers of state neglect are violence and, more specifically as Ruth Wilson Gilmore identifies, organized abandonment.

This tragedy represents the violence that is caused both by and through state neglect not only for the victims of the shooting, but also for the person who allegedly killed them.

From what we know, this shooting was not between rivals, but between friends who were regulars as a group at a bar a couple streets over, known to be involved with criminalized drugs. As an employee of the bar stated: “This isn’t even a case of revenge. And a lot of people are going to try and say ‘oh this is a total case of revenge.’ It’s not.”

Neglect as colonial violence

Two of the four people who were killed on Langside were sisters from Lake St. Martin First Nation, a community located about 260 kilometres north of Winnipeg. This First Nation was one of the communities completely evacuated during the flood in May 2011, which displaced more than 7,000 people in total. The Southern Chiefs Organization (SCO) said in a statement that the Beardy sisters were among the thousand people who still do not have homes to return to, more than a dozen years after the flood occurred.

We can't divorce what happened on Langside from the colonial violence of sheer neglect that we know has caused so many other, very preventable deaths.

This event is far from isolated. Many other community members from Lake St. Martin have died since the community was displaced. Revealing a devastating trend, it was reported in 2017 that at least 92 community members have died since the flood. Earlier this year, the body of another member of the Lake St. Martin community, Linda Mary Beardy, was found in the Brady landfill in Winnipeg.

In a statement responding to the mass shooting, SCO Grand Chief Jerry Daniel questions if the sisters would still be alive today if they were not forced out of their home and their community more than a decade ago.

As Grand Chief Daniel also said, “Sunday’s mass shooting is not the first violent incident to hit our Nations because of displacement due to floods, fires, and systemic issues related to colonial policies and inaction.”

Furthermore, Lake St. Martin Chief Christopher Traverse said that this tragedy shows the need for increased support from both the provincial and federal governments to those who continue to be displaced from the 2011 flood, including, as SCO Grand Chief Jerry Daniel also stated, giving First Nations people an opportunity to return to their home communities.

The cycle doesn't break

Jamie Randy Felix, the person who allegedly killed the Beardy sisters, as well as Melelek Leseri Lesikel and Dylan Maxwell Lavallee, has been abandoned by the state in different ways.

Felix’s father, Randall ‘Chummy’ Fagnan, shared that his son was close friends with those killed in the shooting and that he would look out for them when he was “in a healthier state.”

Fagnan says his son is unwell and needs help. The alleged killer reportedly witnessed his twin brother’s murder in 2012, a highly traumatic event for Felix that similarly took place in West Broadway and involved drugs. This trauma compounded with his pre-existing psychiatric disabilities and substance use; Autumn Beardy, one of Felix’s close friends, said his seizure disorder and his struggles with substance use “worked together to fuel and exacerbate his manic episodes.”

Felix slipped through the cracks of the systems he looked to for help.

Beardy also said how he was working hard to live a good life – he was known for working with Strength in the Circle, a support group for young Indigenous men in Winnipeg who have survived the criminal punishment system. But he still had trouble finding adequate mental health support. Beardy related that ‘like clockwork' each December, Felix's struggles would worsen as his birthday, which he shared with his late twin brother, drew closer.

Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs (AMC) Grand Chief Cathy Merrick responded to the mass shooting on Langside, stating that “it is imperative that we tackle the root causes of violence and take proactive measures. [...] By prioritizing mental health support and addictions, we actively contribute to fostering a safer, more compassionate environment for everyone.” She also highlighted the need to “not only prioritize mental health but also intervene effectively before violence unfolds within our homes, Nations, and municipalities.”

AMC Grand Chief Merrick raises an incredibly important point that I wish to repeat: the key to addressing this kind of terrible violence is preventing crises well before they happen. The current way we, as a settler-capitalist society, deal with violence is to respond to it with more violence. The cycle doesn't break.

From punishment to care

If our governments actually care about creating safety – rather than retributive punishment – then they have to address the things that contribute to unsafety for victims/survivors and people who commit harm. They need to shift the focus from punishment to care.

Community members in West Broadway quickly mobilized to care for one another; in a couple of days, a sacred fire was lit and a community gathering was held at Ma Mawi Centre. A few days later, the West Broadway Bear Clan held a vigil outside 143 Langside Street. The event was marked by drumming and song and held space for loved ones to share memories.

These types of grassroots mobilizations are extremely important community-led spaces of mourning, care, and ceremony.

If we want these killings to stop happening in our communities, we need to change how we think about and deal with violence.

In her book, Insurgent Love, Ardath Whynacht identifies the parallels between state institutions like policing, incarceration, and the military and intimate violence (see here for further reading). We know that Felix served in the Canadian Armed Forces for 11 years, a space that he once stated helped change his life after his brother’s death.

Neither his military history, nor the police with its seemingly-limitless budget, did not, and could never have stopped this atrocity from happening. The military, like policing and incarceration do not prevent violence, they are violence and thus perpetuate it.

There’s no question that structural state neglect is at the centre of the tragedy that unfolded in West Broadway. How can we put Felix in prison for the state’s own complete failure to care for him? Incarceration will remove him from his community and supports, and therefore will likely further intensify his mental health issues.

What will prison do for Felix, other than destroy what is left of his spirit? Like the Beardy sisters after the flood, Felix is displaced, cut off, and isolated from community. We need to address the sources of violence, not punish those who need our care and support. What happens if/when Felix ever gets released? The cycle of state neglect is bound to continue. This is social murder.

We need to drastically shift funding allocations from policing and incarceration towards universal mental health care, accessible housing, and harm reduction-based supports to reduce violence. We need decriminalized drugs, safe consumption sites, and drug testing. And we need police-free wellness checks with trained, trauma-informed care workers.

We cannot continue to fight violence with violence. We need to support everyone in our communities, not punish and incarcerate them.