Revealing the relationship between police violence and the strengthening of police powers

Winnipeg’s municipal election is quickly approaching. Along with a chaotic mayoral race and a deeply uninspiring crew of candidates for councillor, this reality guarantees us one thing: almost every aspiring politician pretending the city has no real control over the Winnipeg Police Service (WPS).

We saw this narrative crop up across the country during the fascist occupations euphemistically dubbed the “freedom convoy” earlier this year; as cops refused to enforce basic traffic laws — instead choosing to rack up their pensionable overtime by providing unofficial security for the occupiers — city councils across Canada claimed that they were helpless to do anything as they couldn’t direct police operations. This same talking point is also constantly invoked by councillors in response to community members criticizing police.

In Winnipeg, the main justification for this apparent powerlessness is the provincial Police Services Act (PSA), which governs all policing in Manitoba. This governance includes the WPS, of course, but also the RCMP’s provincial and municipal policing programs and smaller police departments like Brandon or the Manitoba First Nations Police Service, which services eight First Nations communities.

Recently, following several years of intense opposition to police violence led by Black and Indigenous communities, the PC government amended parts of the legislation in a supposed demonstration of police reform. Yet for the most part, there has been little critical scrutiny of the PSA, what it actually prescribes, or what the new changes mean.

This piece serves as an explanation of some of the key aspects of the legislation: its history, major institutions, and who actually controls police. In contrast to the reformism of the PSA — which only entrenches police power and funding, and further insulates cops under the false guise of “accountability” — an abolitionist politics that fights for slashing police budgets and refunding community is the only way to achieve true accountability, justice, and community safety.

What is the Police Services Act (PSA)?

The PSA was first introduced in 2009 as Bill 16 by the provincial NDP government. It replaced the ancient Provincial Police Act that was "badly outdated and in need of review." The new 48-page piece of legislation includes more than 100 different sections divided into major categories including administration, responsibility for providing policing, municipal and First Nation police services, and investigations into police conduct.

Most importantly, the PSA created, or authorized the creation of, several new major roles and institutions including a provincial director of policing, Manitoba Police Commission, Independent Investigation Unit, and municipal police boards (including the Winnipeg Police Board). Police boards became mandatory, rather than voluntary, and police were no longer authorized to investigate allegations against other police (directly, at least).

It also enabled the creation of a “community safety cadet program,” such as the WPS’ blue-shirted “Auxiliary Force Cadets” that started in late 2010; cadets are lower-paid, entry level civilian pseudo-cops assigned to menial tasks like directing traffic, foot patrols, and conducting surveillance, representing a “civilianization” process that ultimately widens police powers.

As one Winnipeg Free Press reporter optimistically proclaimed at the time, these “sweeping changes” would “effectively tear down the ‘blue wall’ that has separated many Manitobans from their police officers.” Yet the legislation was clearly prejudiced in favour of policing and criminalization from the outset, with the introductory preamble claiming that “police services play a critical role in protecting the safety and security of Manitobans” and that “public safety is enhanced as police services become more representative of the communities they serve.” At no point in the legislation does the power or authority of policing come into question.

Further, the PSA mandates the Minister of Justice to ensure “adequate and effective policing is provided throughout Manitoba,” with a recent review of the legislation describing that mandate as its “fundamental purpose.” However, as noted in the same review, “nowhere in Manitoba’s legislation or regulations is ‘adequate and effective policing’ defined.” This means the essential metric of the legislation, and decisions regarding policing more generally, is entirely up to the discretion of the provincial justice minister.

Why was the PSA introduced?

Most directly, the legislation was developed in the wake of the 2008 Taman Inquiry, launched in response to a botched investigation led by the East St. Paul police department (along with the prosecution and sentencing) into the death of Crystal Taman, who was killed by a drunk driver and off-duty WPS officer, Derek Harvey-Zenk, in 2005. There was immense anger at how Taman’s death was handled and the NDP harnessed it to introduce long-considered changes.

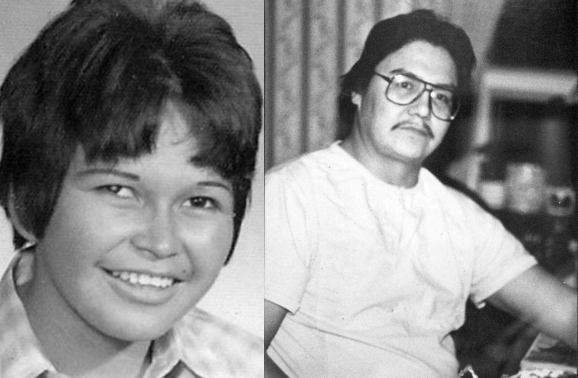

But this push for police reform had a much longer history. Some of the PSA’s key features, like a supposedly “independent” unit to investigate police violence, can be traced back to recommendations from the landmark Aboriginal Justice Inquiry (AJI) of 1991 that re-examined the killing of Helen Betty Osborne in 1971 (which wasn’t properly investigated until 16 years after the murder and only led to one conviction despite there being four suspects) and J.J. Harper in 1988 (who was shot and killed by a Winnipeg Police officer).

The subsequent AJI implementation commission of 2001 issued many recommendations including creating regional Indigenous police forces, increased hiring of Indigenous people to existing police forces, making “major improvements” to the Provincial Police Act, and developing an “an effective and independent oversight mechanism.” As detailed by Ruth Nortey in the recent book collection Disarm, Defund, Dismantle, the first civilian oversight agency in Canada was introduced in Ontario in 1990 due to calls to action by the Black Action Defense Committee that was organizing against police killings in Toronto.

There were also several police killings of young Indigenous men and teens in the years leading up to the introduction of the PSA in Manitoba, including Matthew Dumas in 2005 and both Michael Langan and Craig McDougall in 2008 (McDougall was Harper’s nephew). As Nahanni Fontaine, then the director of justice for the Southern Chiefs’ Organization and now MLA for the St. Johns riding, explained about the introduction of the PSA in 2009: “For me, it's so important ... just to recognize the substantial contribution of our community and leadership in trying to bring forward said changes over the past 17 years. Otherwise we intrinsically negate and dismiss the death of J.J. Harper and the impact his death had on all policing relations and the framework for all justice that occurs in all Manitoba.”

The push for the PSA also came from years of advocacy from community organizations such as the Inner-City Safety Coalition for police reforms and oversight in the form of a municipal police board. The PSA also emerged within a broader shift towards a culture of so-called “community policing” in Winnipeg, which has introduced school resource officers (SROs) in North End schools and “Operation Clean Sweep” in the West End, premised on the “aggressive enforcement and a highly visible police presence were used to suppress general street violence and disorder.”

What did the new institutions actually do?

As mentioned, the PSA introduced three major institutions: the Manitoba Police Commission (MPC), Independent Investigation Unit (IIU), and police boards for every municipal police force. Each of these institutions promised, at least on paper, to provide greater oversight and accountability of police through third-party oversight. It also created the role of “director of policing,” a Manitoba Justice employee responsible for overseeing and supervising all police services and reporting directly to the justice minister (it's unclear who this director is at the moment).

The MPC became the umbrella oversight organization that all municipal police boards are accountable to, response for such things as conducting trainings for all members of police boards and civilian monitors for IIU investigations, as well creating policies and procedures for boards. Further, the MPC was tasked with conducting studies and providing “advice” to the justice minister about police operations, conduct, and standards.

Next, the PSA mandated the establishment of a police board for every municipality that operates its own police department. Quite crucially, this doesn’t include the provincial RCMP or municipalities that contract their policing out to the RCMP, such as Steinbach, Portage la Prairie, and Thompson. It does, however, include the tiny municipal police forces of Victoria Beach and Cornwallis, each of which only have one permanent police officer.

Where it became required, police boards were assigned with providing “civilian governance” and “administrative direction and organization” for the police force in question. This includes hiring and directing the police chief, establishing priorities for the police force, and purportedly ensuring community representation and interests. The police board is also responsible for providing police budget estimates and information to council for deliberation.

The main selling point of police boards was the alleged protection of police oversight from politicization by councils. However, police board members are still either appointed by council or the province — with councillors often chairing the boards — meaning there is far less independence from pro-police political interests than claimed.

Finally, the IIU was created to conduct investigations into police violence if a death or “serious injury” occurs, or if a cop has “engaged in specified unlawful conduct.” Unlike the previous era of police investigating police, the IIU is appointed a “civilian director” responsible for hiring and overseeing investigators.

While the civilian director cannot be a former cop, the investigators are required by law to have worked as a police officer or be “a civilian with investigative experience.” Although this has recently changed, this meant that active police officers were often “seconded” to the IIU as investigators while still employed by the police force; as justice minister Dave Chomiak explained, “Investigators don't sort of grow on trees,” which the Free Press’ editorial board responded to by arguing “Mr. Chomiak speaks like a man who has listened to those who argue that entrusting investigations to outsiders would be a mistake.” The PSA also introduced the possibility of the MPC assigning “civilian monitors” to IIU investigations.

Importantly, the IIU cannot unilaterally lay charges, but “must forward the results of the investigation to independent legal counsel for advice” after the investigation has been concluded. As we’ll see shortly, this often results in charges not being pursued.

How was the PSA received at the time?

With some degree of caution, to be sure.

For starters, it was clear that cops had their hands all over the legislation. The province had reportedly consulted with police across the province “for more than a year on the changes.” However, as detailed in a 2011 Manitoba Law Review article about the PSA, these were “informal, non-public” consultations, and police didn’t make presentations in the public committee hearings like every other interest.

As a result, it was argued that “the public remained in the dark and was rendered incapable of scrutinizing the perspectives of these groups on the bill and how, if at all, the informal consultations with police impacted the shape of Bill 16.” Unsurprisingly, police appeared to favour the new legislation, with WPS chief Keith McCaskill describing it as “long overdue” and suggesting that it would help reverse declining public confidence in policing.

Another immediate concern was about the supposed “independence” of the new IIU. As Tom Simms of the Community Education Development Association explained: “One of the key shortcomings of the legislation is that the investigators will be existing and former police officers. Simply put — this does not pass the smell test.” A related source of criticism at the time was that the roster of “independent prosecutors” made by the province for IIU-related prosecutions included Marty Minuk, the same lawyer who botched the prosecution in the Taman investigation.

Both of these critiques challenged the alleged impartiality of this legislation and highlighted the bill’s implicitly pro-cop agenda.

What happened next?

There were incredible delays in actually getting the new institutions off the ground.

The PSA became law in 2009. However, the nine appointments to the Manitoba Police Commission weren’t made until early 2011. In keeping with the aforementioned trend of police collaboration, the first head of the commission was criminologist Rick Linden, architect of the ultra-draconian Manitoba Auto Theft Task Force, while three of the commission members were former cops (including a former deputy chief of the WPS).

Later that year, the first executive director of the commission was named: Brian Cyncora, a long-time WPS officer. By this point, some members of the MPC were becoming restless and went to media with their complaints: two commission members told the Free Press, anonymously, that “no one knows what they’re doing” and that “our best effort until now just hasn’t been good enough.”

Next were the police boards. Winnipeg’s police advisory board, established in 2007, was dissolved at the end of 2009 in anticipation of the new provincially mandated boards. But by the end of 2011, it was reported that “the province appears nowhere close to bringing them in.” In mid-2012, justice minister Andrew Swan set a deadline for the end of the year for every municipality with its own police force to establish a police board.

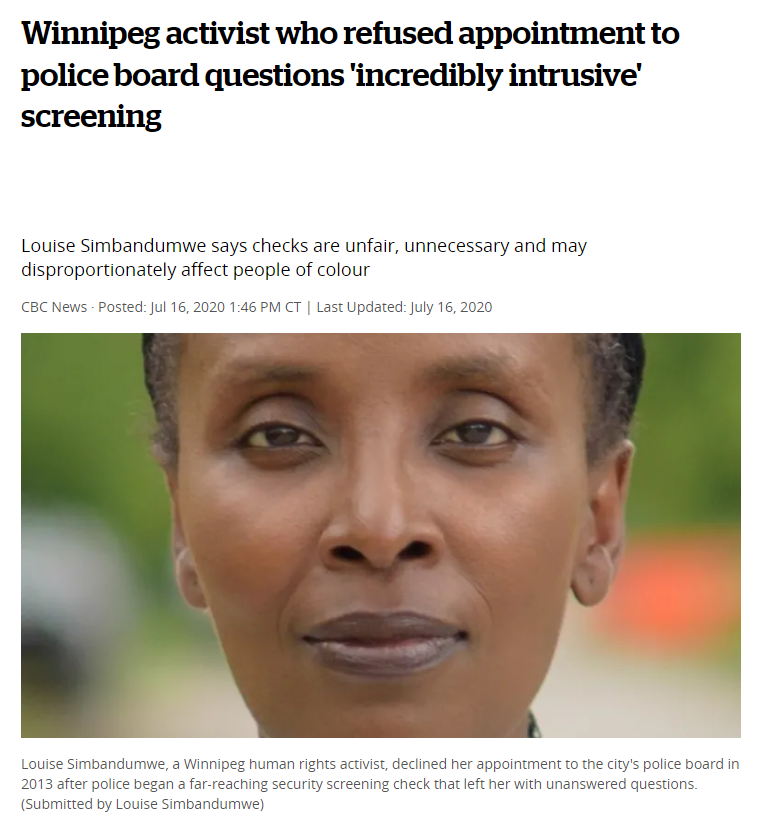

To nobody’s surprise, this deadline didn’t end up mattering. In late 2012, Winnipeg and the province became locked in a petty fight over who should cover annual costs of the city’s police board. A few months later, the Winnipeg Police Board appointment process became embroiled with its own set of issues, with prospective board member Louise Simbandumwe challenging the process, which saw the WPS conducting security clearances into people tasked with overseeing them. As Simbandumwe put it at the time, this represented a “pretty profound conflict of interest” that “does undermine the independence of the board.”

Another board appointee resigned only a few weeks later, further delaying the board’s inauguration. The Winnipeg Police Board didn’t end up starting its work until June 2013, which WPS chief Clunis responded to by stating that “I don’t think there will be a significant difference” in reporting to the board, rather than a city committee as previously required.

Lastly, the IIU started to come into being with the March 2013 appointment of Zane Tessler as its first civilian director. Tessler had worked as a lawyer since 1980, first in criminal defence but later as a “star Crown prosecutor” for the Manitoba Prosecution Service, eventually overseeing the management of new prosecutors. Echoing McCaskill’s own description of the PSA in general, Tessler said upon being hired that “the IIU will play an important part in reinforcing the confidence of Manitobans in our police services.”

However, it took until mid-2015 for the IIU to actually begin its work. Headed up a former Calgary Police officer, the investigative team was composed of personnel from the RCMP, Canadian Armed Forces, London’s Metropolitan Police, and the WPS. A half-decade after the PSA became law, its major institutions were finally all in motion.

So how’s it all gone since?

About exactly how you’d expect, given that each of the institutions were quite clearly designed to boost legitimacy for police rather than actually reduce police power, funding, and violence.

Manitoba Police Commission

The Manitoba Police Commission (MPC) very clearly only exists because it’s legally required to. Its website is barely updated and doesn’t even disclose who the executive director is (it appears to still be Andrew Minor, a longtime RCMP appointed to the MPC in 2013). It’s now chaired by renowned lawyer David Asper, with a correctional officer as vice-chair and other commissioners including a former RCMP officer/commissioner of the Law Enforcement Review Agency (LERA), a Thompson firefighter, and a former president of the Manitoba Metis Federation (MMF).

The MPC runs police board and police chief trainings (although there haven’t been any public updates about this since early 2017). It also continues to perform a regulatory function of police boards, such as when it informed the Winnipeg Police Board in 2018 that the use-of-force policy was “out of sync” with the PSA.

In late 2019, the MPC submitted an awful report to the province about “downtown safety” that recommended further privatization and securitization of the city, including “improved use of closed-circuit surveillance cameras and stronger enforcement of panhandling laws." Other recommendations, such as imposing mandatory treatment on "chronic offenders" and integrating facial recognition technology into downtown surveillance, was blasted by critics. These types of interventions, with security camerasr recently taken up by the police/True North front group “Downtown Safety Community Partnership,” are manifestations of racist and anti-poor logics that criminalize visible poverty.

Three of the seven “news releases” that have been published on the MPC’s website since 2009 were about that report. When it does any work at all, it's deeply reactionary in nature.

Police boards

The police boards are more intriguing — and, frankly, worrisome. Although supposedly designed to provide arms-length “civilian” oversight of police, they instead function to add an additional layer of bureaucracy to budget deliberations and provide a highly useful cover to both police and council by working to absorb and neutralize criticism.

Far from performing any kind of genuine “civilian oversight” role, police boards serve as blatant extensions of council and provincial interests while providing crucial legitimacy to police in the face of rising criticism. In 2016, for instance, the new provincial PC government (which appoints two members to the Winnipeg Police Board) replaced renowned Indigenous leader Leslie Spillett and retired school principal Angeline Ramkissoon with a businessman and a former Conservative candidate. As Spillett explained in a statement, she was not notified by the province of the decision and found out via Facebook, adding that "as a Indigenous person in Winnipeg I am always concerned when the voices and perspectives of Indigenous people are diminished or excluded in these processes and I think that is unfortunate that is the case with the WPB."

The Winnipeg Police Board is currently chaired by ardently pro-cop councillor Markus Chambers, who frequently responds to critical delegations with obvious scorn and contempt. Despite the official requirement of the police board to reflect community desires and interests — a significant chunk of which has been pushing for defunding for years — it serves as a rubber stamp committee for police budgets. As criminal justice professor Bronwyn Dobchuk-Land argued in 2019, the Winnipeg Police Board is “more interested in justifying police spending and taking police demands at face value rather than providing a public check and balance.”

The cops themselves know the police board has no real control. In 2015, the WPS bought its $343,000 armoured vehicle — which they don’t want you to call a “tank” — without even notifying the board. Despite the criticism by Simbandumwe in 2013 of the WPS conducting security clearances of prospective board appointees, the exact same situation played out in 2020 when councillor Vivian Santos — who had recently been publicly critical of police funding — was forced to resign from the police board after the WPS rejected her security clearance. As Simbandumwe told media in 2020 following the Santos situation: “The only conclusion that I can come to is that the police really want to have some measure of control over who sits on the board, and that's their way of exerting it.”

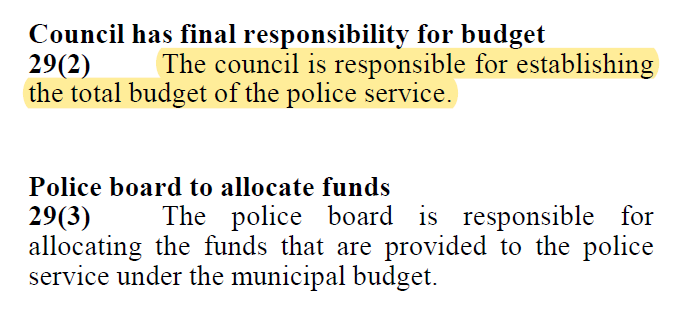

More than anything, the police board serves as a vital tool to insulate police budgets from democratic input. Although the PSA clearly states that “council is responsible for establishing the total budget of the police service,” municipal politicians constantly suggest that this power is actually in the hands of the police board. Through this, the responsibility for council to administer cuts to the police budget is obfuscated. Even Brian Mayes, a deeply pro-cop councillor, resigned from the police board in March as “the board’s relationship with city council has become dysfunctional, with ongoing arguments over respective roles and jurisdiction.”

Key to this process has been the systematic blocking and undercutting of participation in the police board by racialized women who might offer a more critical perspective on policing than desired, including Spillett, Simbandumwe, and Santos. The combination of weaponizing police security clearances (which clearly discriminate against people from poor and racialized communities subjected to far greater police surveillance and harassment), council and provincial appointments, and jursidictional mystification have maintained board power in the hands of police and adjacent interests.

Independent Investigation Unit

Of all the PSA’s institutions, it’s the Independent Investigation Unit (IIU) that has been most thoroughly obstructed, compromised, and exposed. As already mentioned, there were concerns voiced at its time of inception about the involvement of current and former police officers in investigations, given the IIU’s supposed mandate was to provide “independence” from police departments exerting influence. In 2016, only a year after its creation, Robert Taman — widower of Crystal Taman — resigned from his role as commissioner with the Manitoba Police Commission due to concerns that the IIU still meant that police were investigating themselves.

The depth of the issues, however, wasn’t fully exposed until 2018 with a devastating Free Press series led by Ryan Thorpe into the IIU. Through eight months of investigation, Thorpe found that the WPS had “long resisted the IIU’s mandate, either by refusing to co-operate with investigators or stifling civilian complaints entirely.” Thorpe also found that Manitoba Justice hadn’t publicly released the IIU’s annual reports for the previous two years and had never conducted an internal review of the unit.

This trend of police obstruction of the IIU included 74% of subject officers (those involved a death, injury, or offence that could result in criminal charges) refusing to cooperate with investigators and the WPS not even notifying the IIU of several major accusations. In fact, when it first started up, the WPS’s professional standards unit (PSU) — previously responsible for internal investigations of complaints — “operated as if the IIU didn’t exist” and “kept criminal accusations against officers from the agency responsible for investigating them.”

Despite claims that these issues merely represented “growing pains” for the IIU, conflicts between the unit and police departments have continued in the years since. In 2019, the IIU launched a lawsuit against the WPS due to its blocking of cadets handing over notes for an investigation into the 2018 police killing of Matthew Fosseneuve. Last year, the RCMP fought the IIU in court over a similar request concerning the handing over of electronic reports filed after police assaulted a man in Thompson (the man later ended his life).

While the number of officers charged by the IIU has increased from its first few years, with 17 charges against nine officers laid in 2020-21, this remains a low proportion of investigations conducted, with 59 concluded in that window. No charges have come from investigations into policing murders of civiliansFor example, the IIU didn’t charge the WPS officer who shot and killed Eishia Hudson in April 2020. The IIU charging an officer obviously doesn’t guarantee a conviction, either, especially given the Manitoba Prosecution Service’s well-known tendency to absolve cops of any repercussions.

As Robert Taman told Thorpe during the 2018 investigation: “Nothing has changed. It’s like nothing has changed at all.” In spite of all the bluster about police reform and accountability with the PSA, nothing has changed at all.

What recent changes did the province make to the PSA?

An update to the PSA had been in the works for years, and was discussed frequently in the wake of the 2018 Free Press investigation. At the time, both the provincial NDP and Liberals called for a review of the legislation, with NDP justice critic Nahanni Fontaine stating: “If we need to strengthen the legislation then let’s strengthen it. If we need to look at the structure of the IIU then let’s look at it.” The Pallister government committed in that year’s Throne Speech to “modernize the Police Services Act … in order to support innovative solutions and improve policing services.”

In 2019, the PCs issued a request for proposal for a consultant to review the PSA. This $265,700 contract was awarded to the “Community Safety Knowledge Alliance,” an innocuously titled Saskatoon-based non-profit chaired by the chief of Edmonton Police and whose CEO was former assistant commissioner of the RCMP. The organization consulted with “provincial and municipal government officials, chairs and members of police boards, chiefs of police, police associations, and representatives from IIU, LERA, and the [Civilian Monitor Program],” along with other groups including prosecution services and First Nations and Métis organizations.

The report, expected by mid-2020 but delayed until November, contained 70 recommendations. In March 2021, the provincial justice minister said that turning these recommendations into new legislation would be further delayed, citing the recent IIU report that cleared the officer who killed Eishia Hudson and the need to further consult with Indigenous leaders.

In May of that year, Winnipeg mayor Brian Bowman slammed four of the report’s recommendations — an arbitrator handling budget conflicts between the WPS and council (which already happens), the WPS replacing the board’s role as community liaison, the police board replacing the city as the employer of police, and the province getting two extra picks for police board members — as “a takeover of a local police service by the provincial government.”

So what actually changed?

Very, very little. Astonishingly little, actually, given the immense public protest and pressure since the intense summer of 2020. The province didn’t even bother to clarify what “adequate and effective policing” means, continuing to leave it entirely up to the justice minister.

In fact, police power has only been strengthened through the changes, with the province clearly leveraging the lengthy bureaucratic process to smuggle in several expansions to policing scope, as well as working to bolster the legitimacy of police through minor but flashy reforms.

The PSA was mainly amended through two bills in June 2021: Bill 7, which focused on the IIU, and Bill 30, which focused on the PSA and Law Enforcement Review Amendment Act (which governs LERA, the toothless agency for complaints against police violence that aren’t investigated by the IIU).

Bill 7:

- Ended the practice of current police officers being allowed to work as IIU investigators

- Established a position of “director of Indigenous and community relations” tasked with liaising between the IIU and Indigenous communities, including hiring Indigenous people to act as a “community liaison” with families and loved ones of people harmed by police violence (it is important to emphasize that this change was welcomed by several Indigenous organizations)

- Clarified rules around police reporting of serious incidents to the IIU, removing the clause of “as soon as practicable” and replacing it with the unit being “immediately notified”

- Required witness officers (not subject officers) to fully comply with IIU investigations

Bill 30:

- Extended the deadline to submit a complaint to LERA from 30 days after the incident to 180 days (an Indigenous transit driver recently traumatized by WPS had her LERA complaint rejected because it was filed a day after the 30-day deadline)

- Established a “Manitoba Criminal Intelligence Centre” to collaborate with police departments and “develop their criminal intelligence collection and analysis capacity”

- Requiring the director of policing to establish a provincial “code of conduct” for police

- Encouraged the creation of “standards” to be developed for policing and “dealing with criminal intelligence”

However, the PSA was also amended through a bill quietly passed in June 2019 that wasn’t brought into force until 2021, along with the other changes. Bill 17 created a new class of private quasi-cops called “institutional safety officers” at hospitals and post-secondary institutions. Hired as licensed security guards, these “officers” will be trained by police departments and permitted to make arrests and carry batons and “aerosol weapons” (like pepper spray).

So in sum, the province made small tweaks to the IIU and LERA, created a new “criminal intelligence centre,” requested a code of conduct and standards for police, and permitted greater powers for security guards.

That’s it. Those are the long-awaited changes.

What wasn’t changed?

Nothing was changed about the general attitude or approach to policing. The Manitoba Police Commission remains useless. The boards are still obstructing genuinely democratic control of police, and the IIU is still run by a former Crown prosecutor with an investigative team of mostly former cops, while “subject officers” facing charges are still not required to comply with investigations due to bluster over “self-incrimination” (meanwhile, basically every other regulated profession requires full compliance or they lose their ability to work in it).

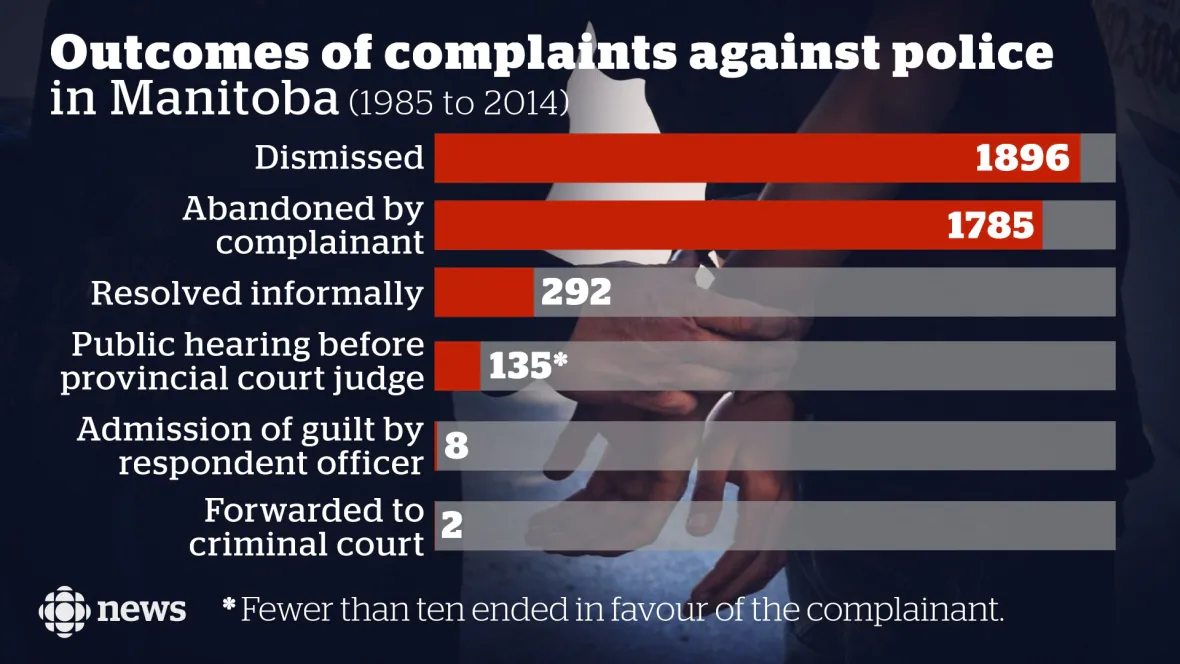

Aside from the deadline extension, nothing about LERA was improved either. We’ve known for years that LERA is completely ineffective, with a 2016 investigation finding that only 3% of complaints (135 of more than 4,300) had ever proceeded to a public hearing before a judge and fewer than 10 of those ended in favour of the complainant.

Complainants often can’t afford legal counsel and the review process requires witnesses or evidence (which many people understandably can’t provide). As a result, most complaints are abandoned or withdrawn. Further, LERA is reportedly underfunded and understaffed. The PCs pledged to address the “outdated” aspects of LERA — and then, unsurprisingly, barely did anything about it.

But it’s important to be realistic about the function of the IIU and LERA. Even if they weren’t staffed with ex-cops, or if “subject officers” were required to comply with investigations, or if every complainant had guaranteed legal counsel, or if independent prosecutors (rather than the Crown) were retained for advice on charges, many cops would continue to get away with incredible harms at the end of the day. This certainly doesn’t mean that such changes shouldn’t be pushed for — but that we should be aware of the serious limitations of these kinds of reforms outside of a broader abolitionist struggle.

Section 25 of the Criminal Code excuses almost all police violence on the basis of the officer’s subjective judgment, permitting any use of force if the cop “believes on reasonable grounds that it is necessary for the self-preservation of the person or the preservation of any one under that person’s protection from death or grievous bodily harm.” This protection is what has been described as a “get off free card for cops.” While police will very occasionally be charged for offences like assault, dangerous driving, or perjury, a vast majority of incidents are unpunished..

The entire system remains totally rigged in favour of police power and funding.

So what can the city do about this?

It all depends on your conception of politics and struggle.

The province clearly holds a great deal of power over municipalities when it comes to policing (or anything, really). As discussed, it’s up to the justice minister to determine what “adequate and effective policing” even means. If the minister decides that this entirely arbitrary metric isn’t being fulfilled by a police force, they can directly intervene and suspend its operations, replace it with the RCMP or another police force, appoint an administrator to oversee operations, remove and replace the police chief, remove police board members, and “take any other steps that the minister considers necessary to provide adequate and effective policing services in the area in question.” All of the costs for this would be borne by the municipality, as well.

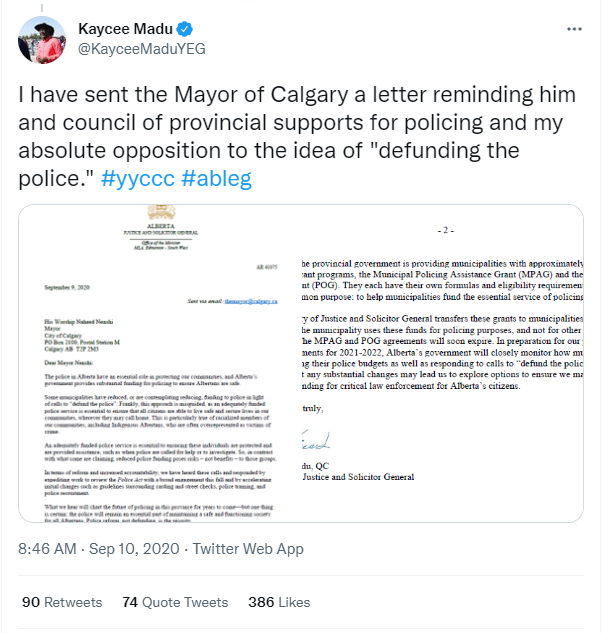

This is an obscene amount of control. We’ve already seen this kind of power flexed in recent years in other provinces, including BC’s director of policing ordering Vancouver to increase the police budget by $5.7 million and Alberta’s justice minister invoking the province’s authority to force Edmonton to develop a “public safety plan” for the downtown. In 2020, Alberta’s former justice minister also threatened to cut funding to municipalities and redirect it to police forces if cities cut police budgets. The same could clearly happen in Manitoba if Winnipeg or any other municipality starts to aggressively spar with their police force.

At the same time, there is considerable latitude with the legislation and political climate for major contestation at the municipal level. For starters, the basic definition of “adequate and effective policing” can be heavily politicized and problematized, especially given the lack of clarity in the legislation itself. Building on that, the clear articulation in the PSA that “council has final responsibility for budget” should be consistently leveraged to rebuff false claims that the police board sets the police budget (again, the police board exists to receive a proposed budget from police and make recommendations to council, but it’s entirely up to council to set the budget and for the board to allocate those funds).

The current make-up of police boards is overwhelmingly in favour of police, with pro-cop councillors usually chairing and dominating meetings. There’s nothing in the legislation or regulations that necessitates this, however. Appointees can be basically anyone while the board itself elects the chair and vice-chair. The de facto domination of the police board by pro-cop interests should also be challenged, or at least not taken as preordained in the written rules. Its legislated mandate to “ensure that police services are delivered in a manner consistent with community needs, values and expectations” is also a significant window of opportunity to organize around, including in a possible push for directly elected board members.

The point here isn’t that we should naively fantasize about police reforms clearly introduced to shore up police power being sneakily leveraged for abolitionist gains. Such efforts will undoubtedly continue to trigger enormous backlash from pro-police interests. But the supposed fear or constraints of the provincial government cracking down on the city shouldn’t artificially restrict the scope of our struggles.

Instead, these conflicts and contradictions should be embraced head-on, with full knowledge that most of what these people tell you about the rules are arbitrary, disingenuous, or entirely fabricated. Reactions by the province or other interests should be further politicized and used to advance radical aims, not shied away from. It’s obvious that almost all politicians are cynical careerists who use jurisdiction as a pretext for their inaction. In this case, we must at the very least call them on their bluff and continually ratchet up the pressure on them to cut police funding.

The abolitionist horizon

At the end of the day, there’s simply no way around it: the only way to reduce police killings, abuses, and harms is to defund and abolish the police. Every increase to the police budget, 85% of which goes to salaries and benefits, guarantees more killings, abuses, and harms. The notion of “police oversight” within a context of ever-rising budgets is completely farcical and profoundly insulting to the victims and survivors of police violence, particularly given that IIU and LERA are fundamentally made to absolve cops of almost any use of force.

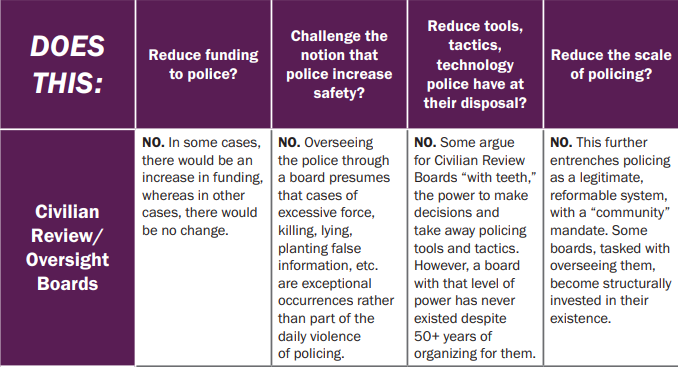

Our collective liberation does not ultimately reside in the strengthening of the PSA, the democratization of police boards, or the diversification of investigators into police violence (so that former cops are no longer investigating cops). Such reforms would be beneficial, probably, but only in the context of aggressive cuts to police budgets and redirections of funding to life-sustaining services and infrastructures that actually keep people safe.

The PSA, MPC, police boards, IIU, and LERA all exist to obscure this reality and maintain the illusion that police can be successfully regulated into compliance while spending millions of dollars more every year on their operations. Knowing that, our demands must remain laser-focused on cutting the police budget — and in turn powers and resources — rather than thinking that more reforms will work.

As Mariame Kaba reminds us, we must oppose all proposed “reforms” that give more money to police, focus on technology (like body cameras), or emphasize “dialogue” with cops. As she writes, “all of the ‘reforms’ that focus on strengthening the police or ‘morphing’ policing into something more invisible but still as deadly should be opposed.”

At the same time, Kaba identifies several reforms that can build the movement towards abolition. These include proposals for reparations to victims of police violence and their families; civilian accountability boards that are elected, independent, and with the power to fire and hold officers accountable (although she notes there are serious limitations and dangers with this approach); and for data transparency about things like arrests and use of force. Kaba also notes the possibility of “proposals and legislation to disarm the police” and “proposals to simplify the process of dissolving existing police departments,” which would require a radical reconstitution of the PSA in Manitoba.

This fight remains most relevant at the level of city council, especially given the impending municipal election in Winnipeg. Councils set the budgets for police and it’s essential to force candidates for mayor or council to feel the heat on this clear demand. We can also further politicize the Winnipeg Police Board, including the biased appointment and chairing process, clear proximity to police interests, and obfuscation of its role. While municipal politicians will always retreat to the “jurisdiction” excuse, the reality is that they can take a far more outspoken role about provincial and federal rules, like the recent (failed) push to request decriminalization of a small amount of drugs from Health Canada.

At the same time, a provincial election is on the horizon as well, scheduled for late 2023. This will also be a major moment of prospective politicians making big claims to caring about “police oversight” and such. The province ostensibly has the power to rewrite the PSA along very different lines, including setting the frameworks (or very existence) for the MPC, police boards, IIU, and LERA.

For instance, the PSA could hypothetically be amended to restrict city councillor membership or chairing of police boards to enable less council interference, reconstituted to allow direct elections of board members (like school trustees), require “subject officers” to comply with IIU investigations, or for all LERA complaints to be matched with free legal counsel through a greatly expanded Legal Aid.

With that said, it will be crucial for abolitionists to exercise ruthless criticism of appeals by all parties to existing reformist institutions. Like at the municipal level, the demand must be for a roadmap to defunding and abolition, and the only use for such institutions should be to enable such a transition (this should also include cutting the annual $20 million subsidy provided to the WPS by the province). If the PSA is to serve any function in this transition, it should only be to empower municipalities to radically reimagine community safety without the province staging a retaliatory coup.

Such alternatives have been widely discussed in Winnipeg and many other places. They include, but are certainly not limited to, high-quality public housing, safe supply and harm reduction, non-violent crisis intervention with actual skills in conflict resolution, food security, mental health and substance use resources, income supports, and much more. These services and infrastructures, are the only future of safety in Manitoba, not more clearly failed police reforms. As a result, the only future of the PSA is the replacement of it — along with the MPC, police boards, IIU, and LERA — with a politics of alternative possibilities. We’re no longer talking about a “police services act” but something utterly new and distinct.

The PSA was born out of crisis situations caused by police, with new institutions seen as the remedy — or at least stopgap — for some of their worst excesses. A decade later, we have more than enough evidence that these institutions only exist to insulate and expand policing. Further attempts of police reform are meaningless without drastic and immediate cuts to the police budget. The PSA and its various institutions should ultimately be understood as obstacles to this struggle that have to be abolished along with the police in all of its forms.