Over the last two decades, experts argue that policing in Canada has become increasingly militarized in terms of tactics, strategies, and technologies. The use of police helicopters is but one example of this shift towards more aggressive approaches to policing.

Today the deployment of military tactics in policing is widespread. It is now standard for all major Canadian cities to own and employ police helicopters, armoured personnel carriers, drones, and increasingly mobilized (and militarized) tactical teams.

Yet, also in the last two decades, crime rates in Canada have been steadily decreasing. Instead of reflecting the ‘success’ of policing, criminologists understand crime data like this as functioning to both justify the increasingly broad role of policing and advocate for more tools of surveillance and control (Klick and Tabarrok 2005; Paternoster 2010; Weisbrud et al. 2006). Understood this way, crime rates thus become a key component in a self-fulfilling (and never-ending) cycle of budgetary expansion.

This logic also explains why decision-makers across the country continue to arm the police with new and more aggressive military-style technologies.

The Winnipeg Police Board recently announced it is interested in a $10-million pilot project in 2022 for body cameras. In a recent WPCH blog post, E. R. Gerbrandt articulates that technologies much like the helicopter, body cameras will not ‘fix’ policing “because the problems are embedded in the founding principles of policing itself: to protect private property by enforcing colonial control.”

To discuss the implications of such approaches to policing, I interviewed Dr. Kevin Walby, associate professor in criminal justice at the University of Winnipeg. Dr. Walby studies police tactics and strategies, police communications, and private sponsorship of public police. Specifically, we discuss how AIR1, the Winnipeg Police Service (WPS) helicopter, fits in with the overall culture of policing in Winnipeg. We also attempt to debunk a few myths about police helicopters in general.

Winnipeg City Council purchased AIR1 in 2011 for $3.5 million dollars. While its annual operating costs were initially footed by the provincial government, the Provincial Conservatives cancelled the line item specific to AIR1 in 2017. In 2019, AIR1 cost the City of Winnipeg $2.1 million dollars.

In all, Dr. Walby emphasizes that the issues with the police helicopter run deep: AIR1 represents not only a problem in public policy and decision-making processes, but also budget issues that support the entrenched culture of impunity and lack of oversight at the WPS. Worst of all, the police helicopter affects the material living conditions in Winnipeg and inherently contributes to further criminalizing communities that are already being harmed by police presence.

Winnipeggers should be more concerned about this turn toward more aggressive forms of policing and the increasing use of technologies from the military sector in the WPS. Disarming the police is a crucial and necessary step towards abolition. Grounding AIR1 for good is low-flying fruit.

RH (WPCH): How do you think the helicopter fits within the overall culture of policing in Winnipeg?

Dr. Walby: There’s a lot of evidence to show that Winnipeg police culture is paramilitaristic. The WPS are encoding city councillors, local activists, community groups who are speaking out against policing as enemies and as threats. And they will intimidate them, they will get them thrown off of the Police Board. They’re taking aggressive actions against anyone who will speak out against them. This paramilitaristic approach is allowed to flourish in many ways: the strategies, the tactics, the technologies, and the aggressive nature of the officers.

The constant use of the helicopter is one of such examples. The use of AIR1, the WPS helicopter, doesn’t seem to be based on any of the terms of criminal law that might justify it like reasonable, probable grounds. Regardless of having satisfied thresholds of reasonable, probable grounds, they’re out there almost every day, doing laps around the city. It doesn’t seem to be based on any kind of justifiable, criminal law terms like reasonable grounds. To me, that again speaks to the paramilitaristic culture of the WPS.

What do you think that it says about the WPS that nobody is willing to take responsibility for helicopter noise?

There’s a real culture of impunity in the WPS. It’s institutionalized. It’s entrenched. And it pertains to all of their actions and expenditures. Anytime they’re investigated in any way, that’s when we get to truly see the paramilitaristic dimension of the WPS rear its ugly head.

There have been smaller examples from the last year, like where officers go into people’s houses and rough people up without any masks on during the pandemic. And what happens? Nothing.

Whether it’s police violence and killings, or whether it’s the way they kidnap the municipal budget: the WPS wants to be able to act with impunity and they don't want to have any kind of oversight. There have been lots of examples where the few, pithy oversight entities that do exist in the province ask for records or interviews from the WPS, who are able to simply decline.

The fact that the WPS won’t take responsibility for helicopter noise complaints folds into this broader approach that the WPS takes where they are allowed to act with impunity.

What is the worst myth that the WPS tells the public about the helicopter?

Well, there’s a few of them. I’m not sure which one is the worst.

1. The helicopter provides safety.

This is connected to the broader myth that police provide safety for citizens. This is a myth that goes back centuries and functions to provide some camouflage for the real purpose of policing: to buttress or support the existing political and economic order.

If policing was really about the safety of our communities, it would be organized completely differently. People would have much more of a say about how it is organized or whether it exists to the extent that it currently does.

The idea that the helicopter provides safety is a big myth that needs to be busted. If anything, it may do the opposite: it may direct the violence of policing with pinpoint accuracy and military perception to intercept persons who are being treated as enemies or combattants. And it may lead to the ending of their life. So to me, the capability of the helicopter when it comes to safety is exactly the opposite of what the rhetoric is.

2. Other cities have police helicopters, so we should too.

It’s more internal, but police organizations often point to other cities that have this technology to justify why they should also acquire it. The WPS did this when they were pushing for AIR1. But this is truly a faulty logic because it is not informed by any kind of science, inquiry into the technology, or its benefits and its drawbacks. Instead, decisions are made because other cities have set a sort of precedent: for example, if Calgary has a helicopter, if Calgary has a 80-person tactical team, we need it too.

And internal myths, those myths that are not always communicated to the public, are really powerful. We know there is not a lot of oversight on the budget, there is not a lot of oversight on decision-making. So, if the WPS goes to Winnipeg City Council or the Province and says, “Oh, we need two more armoured personnel carriers and we need another helicopter, we need to replace this one because that’s what Edmonton just did.” That’s likely what will happen. Internal myths are important to bust as well.

And it goes back to the overall culture of impunity and lack of oversight. There is no other unit in government that gets to say: “Oh, they have a ten thousand dollar computer in Criminal Justice at Carleton University, we need one!” Nobody else gets to say that.

Nurses, they often stay an extra hour debriefing with the next nurse. They don’t get paid any overtime for that. When their shift is done, it’s done. But if police just happen to find themselves cruising around and they get stuck in a traffic jam on the way back to headquarters, they’re going to bill that as overtime.

It’s total impunity with the WPS and I would say, public police in Canada more broadly.

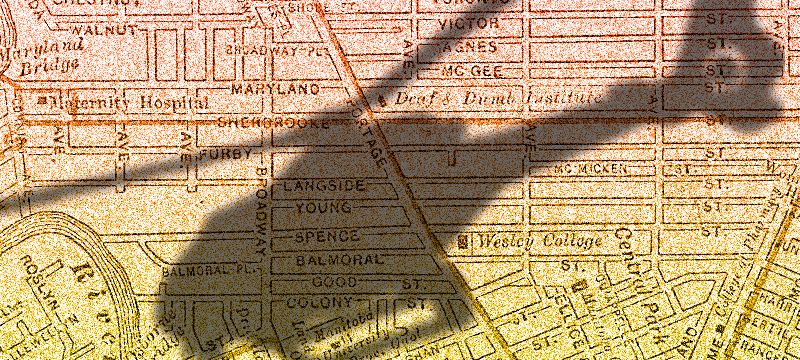

Credit: @karapassey on Twitter

It’s this idea again with the overtime hours and, buying helicopters and armoured tactical vehicles. It’s all setting the precedent: this is what we will need and we will always need more. But the logic turns in on itself because, well, if you’re meant to be providing public safety, with that logic, crime should go down and we shouldn’t need more expansive policing. But, we obviously know that that is not the case and that is not the true purpose for this type of equipment. It functions to justify increasing spending.

That’s what’s so powerful about defunding and abolition movements: policing does not reduce transgressions at all. In fact, in a generational sense, it may actually create a context where community members are criminalized more, which then further destabilizes neighbourhoods. The more that people in a community are criminalized, the higher the rates of divorce are, the lower the rates of education are, which contributes to lower employment rates and then you run into issues around safe and accessible housing.

That’s why there are surgeons and doctors and nurses in Canada who are calling for the defunding and abolition of the police. They’re sick of seeing people show up with injuries from police in their units and they understand it’s actually significantly increasing costs in their unit.

Over time, policing creates the conditions for more transgressions. More distress. More destabilization.

It’s not going to work if, in a decade’s time, the WPS consumes 50% of the city budget. It isn’t going to change that scenario.

And perhaps that’s the biggest myth of all: somehow over time, if we just throw more money into policing, we’re going to live in a healthier society. And nothing could be further from the truth.

Change will occur if we are able to create healthier communities and reduce transgression by increasing funding for housing, addictions services, counselling, community and social development. This will empower people, which will help them access jobs and housing.

How do you see these funds being better spent than on the police helicopter?

There are a lot of community and social development groups right now that are completely underfunded and they’re just scraping by. Sometimes, they have to let really talented people go, people who have talents in conflict resolution and mediation and just caring for people. Like, that is the talent that we need to value more in our society.

I can think of probably a dozen community and social development groups just around my neighbourhood downtown that are totally underfunded right now. If I had the money, I would just give it to them.

I think there’s other models that might be worth looking at: like in Oregon, the CAHOOTS model where you have street nurses, street counsellors, you have people trained in harm reduction and conflict resolution. And you have a big network of them meeting people where they’re at to decrease transgression and distress. We need a big network like that.

Police do not take that approach. They do not have an approach of helping people. They criminalize, which in and of itself is incredibly violent towards communities. Over time, it tears them apart, as we just discussed. There’s a great book by Todd Clear called Imprisoning Communities and he looks like, in a generational sense, how criminalization starts to erode all kinds of indicators in communities over time. And basically, destroys them.

So, to me that’s an important piece to continually hold up: criminalization is not going to help our communities. The police helicopter is not going to help our communities.

The plethora of community and social development workers all around us, who we work with, who we live with, who have incredible skills, they should be funded to actually keep us safe.