Content warning: This post includes detailed descriptions of police violence.

All policing is violence—but the Winnipeg Police Service (WPS) is arguably one of the most violent departments in Canada.

This reputation is nothing new. In 1988, Indigenous leader J.J. Harper was shot and killed by a WPS officer, resulting in the creation of the notable-but-mostly-ignored Aboriginal Justice Inquiry. Between 2000 and 2017, police killed 14 people in Winnipeg with guns and Tasers. Most of the victims were Indigenous.

Such a count doesn’t include those who died while in police custody. Nor does it include the people who were shot by police and didn’t die—like the 16-year-old First Nations teen who was shot nine times outside of a 7-Eleven in late 2019—or those who were severely injured during arrests, like Richard Kakish, who died in 2017 due to massive blood loss several days after being kicked and punched by the WPS during the arrest and processing. And such a count obviously doesn’t include incidents that were not disclosed to police oversight bodies like the Independent Investigation Unit (IIU), an all-too-common occurrence.

Reported incidents of police violence have only got worse in recent years. Last year, in 2019, Winnipeg police killed Chad Williams, Machuar Madut, Sean Thompson, Randy Cochrane, and several more people whose names have not been released to the public (which is typically decided by the loved ones of the victim).

Last year also saw many other severe harms inflicted by the WPS. This included WPS officers putting a man who was experiencing hallucinations on a transit bus into critical condition during arrest (the man died three days later), blowing through a stop sign in a patrol cruiser and hospitalizing six people, publishing a humiliating photo of a man passed out on a city bench (and lying about it), pepper spraying and detaining a cyclist for asking the officer to turn down his high beams in a residential area, hitting a pedestrian with an unmarked police vehicle, and being accused multiple times of sexual assault.

This is only a fraction of the harms, of course. There were 857 use-of-force reports filed by Winnipeg Police in 2019 alone, including 154 Taser deployments.

Unsurprisingly, these harms have not slowed in 2020. While many of these harms have been diligently reported in the media, there is no central repository for this information for 2020. The existence of such a list is crucial to not only see the police harms in one place, but also to understand these harms in relation to each other. After all, policing is not simply a problem of a few “bad apples” but a system of ceaseless violence.

It’s even more important that we remember and account for these harms as the police are receiving increased powers to enforce public health measures relating to COVID-19.

When Winnipeg Police caused harm in 2020

January 18: Police fracture a 19-year-old woman’s left arm during an arrest. Police respond to a call about someone in distress and claim that she is intoxicated at the time.

February 18: Police fracture the tibia and fibula of a man during an arrest following pursuit of an allegedly stolen vehicle. This incident is not reported to the IIU until August.

February 23: Notoriously violent police officer Patrol Sgt. Jeffrey Norman—who has been sued at least eight times since 2005 for allegations including excessive force and destruction of evidence, and who pepper sprayed a cyclist last year—follows and beats an Indigenous teenager unconscious with a baton while off duty, before arresting him for alleged theft from a liquor store. The Winnipeg Police fail to disclose this beating to the IIU.

March 10: Police shoot a 27-year-old man at a home in Charleswood. The man has reportedly been attacking two other people with an “edged weapon.” He dies in hospital shortly after. This is the first death at the hands of the Winnipeg Police in 2020.

April 8: Police shoot and kill 16-year-old Eishia Hudson at the intersection of Lagimodiere Boulevard and Fermor Avenue following a traffic pursuit resulting from alleged theft of liquor and a vehicle. Police claim the vehicle posed a deadly threat to officers and the public. Yet the use-of-force report about the killing is still being kept from the public. Eishia’s parents and loved ones have organized many rallies and vigils since the shooting. Her family is later sent a $250 ambulance bill. In June, the Indigenous Bar Association called for an independent inquiry into the killing.

April 9: Less than 12 hours after the killing of Eishia, Winnipeg Police shoot and kill 36-year-old Jason Collins outside his house on Anderson Avenue (as if the situation couldn’t get worse, it turns out that Jason was the uncle of Eishia’s 14-year-old brother Dominick). Jason was a father of three children. Police say they were responding to a domestic violence call but his family disputes that, with his 15-year-old daughter telling media that while an argument had taken place, nobody was in danger. Jason’s common-law partner also receives a $250 ambulance bill in the mail:

“Winnipeg police came to our property and they shot and killed him and they send you the bill for it.”

April 18: Just over a week after the killings of Eishia and Jason, Winnipeg Police shoot and kill 22-year-old Stewart Andrews. Police responded to a report of a robbery, assault, and broken windows in the Maples. While police claim there is a weapon recovered at the scene, they have not released any further details; the 16-year-old boy who was with Stewart at the time said that he never had a weapon. Stewart was a father of three, including a one-year-old son. His uncle was also shot and killed by an RCMP officer, according to the Free Press.

May 27: During an arrest of a 23-year-old man following reports of a fight between him and a woman, Winnipeg Police fracture the suspect’s elbow. The police fail to disclose to the IIU that the man’s elbow had been broken by a police car driving down the wrong ride of the road and hitting him as he attempted to flee. Lawyer Corey Shefman told the Free Press:

“I have difficulty imagining a situation where ramming your car into a person as they’re running away could be justified.”

June 11: A widely circulated video depicts the brutal arrest of a 33-year-old Cree man pinned on the ground, with police kneeing and repeatedly kicking him. In an unprecedented move, the police’s media release includes estimated values of the property he had allegedly damaged, including a “large granite slab valued at $10,000” and a “window in the concert hall valued at $7,000.” As admitted later by the police on social media, he had been carrying an airsoft gun and what appeared to be a blunt butter or cheese knife. Police claim that kicking him “likely saved his life” and proceed to dox someone who had posted critically about the attack on social media (this part of the incident made it to NBC News). As reported by CBC News, the man grew up in foster care, had his mother go missing in 1999, and recently lost his sister. This incident is not reported to the IIU as it did not constitute “serious injury,” and the IIU has not launched an investigation.

July 11: Police break the right arm of an 18-year-old woman during an arrest. The incident is first reported to the Law Enforcement Review Agency (LERA), which notified police about the fracture. The IIU is not notified about the incident until late September.

October 7: Three police officers shoot a 26-year-old man in the North End, after which he is rushed to the hospital in unstable condition. Police had received reports of an armed man in a nearby alley. Police refuse to disclose what kind of weapon he was carrying. When asked if the man had shot at police, spokesperson Rob Carver said “we don't need to be shot at until we fire back” and “some actions on the part of that male caused our officers to discharge their weapons.” As reported by the Free Press, police repeatedly obstructed the media’s ability to report on the shooting, including taking a phone that had been given to a reporter by an eyewitness and later telling the reporter they had to leave. In response, the Canadian Association of Journalists condemned the police’s interference, stating:

“The actions of Cons. Carver are egregious because they violate not only the media’s right to report freely, but also because they seriously impede the public’s right to know about matters taking place in their community.”

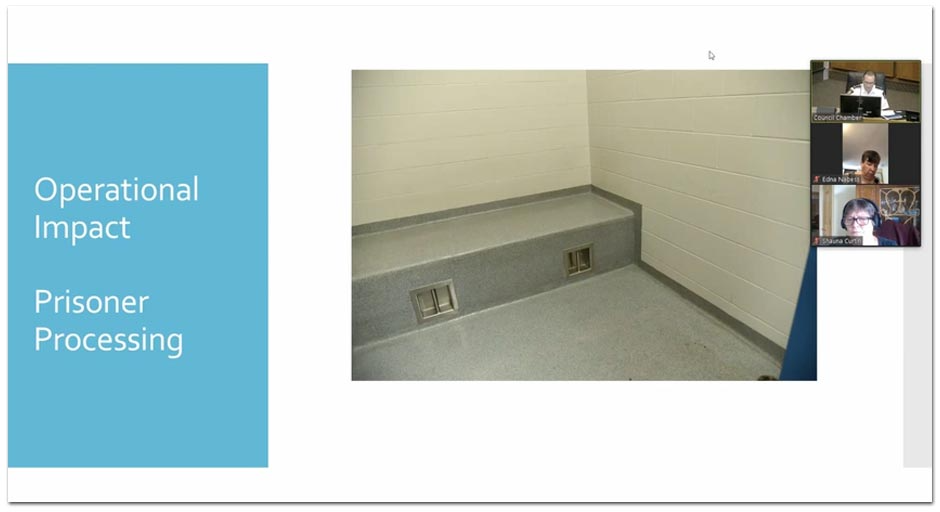

November 4: A 40-year-old man dies while in the Winnipeg Police’s central processing unit. The man had been arrested during a traffic stop related to alleged drug offences. Just over two hours after the arrest, the man is found to be in “medical distress” and unresponsive. He is transported to a hospital, where he is pronounced dead. In June, police chief Danny Smyth told the Winnipeg Police Board that prisoners were being kept at police headquarters in conditions that violated their human rights, including being deprived of toilets, mattresses and food for almost two days. Smyth told the police board:

“We’ve had prisoners urinate in these rooms, defecate in these rooms and vomit in these rooms. The risk of harm to one of these prisoners because of the way they’re being treated at this point has greatly increased.”

This list is far from exhaustive. Incidents happen every single day that result in significant harm but are not disclosed to the IIU. Please contact us on Twitter or Instagram or at our email address if you notice any omissions, and we will update accordingly.

Lead photo credit: Travis Golby/CBC