Winnipeg’s long-awaited transit security force started operations in late February. Consisting of two dozen sworn peace officers — all equipped with batons, handcuffs, and the power to conduct searches, seizures, detentions, and arrests — the security force has since received an outpouring of sycophantic media coverage. Headlines have proclaimed that the officers “get fist bumps from operators, thanks from riders,” are “already making a mark,” and have “have had positive impact.” The head of the force, former WPS officer Bob Christmas, has routinely recounted an incident when officers administered CPR and Naloxone to an unconscious man near Portage Place, and “brought that person back to life.”

Despite its small size, the security force has consistently been framed as already improving safety: not only for transit workers and riders but also marginalized people using bus shelters to sleep or experiencing some kind of medical emergency or interpersonal conflict. This highly favourable narrative is certainly important to cultivate legitimacy in the early days of the force, but even more so to justify future budget increases from the city and province to expand its size and scope. Costing an estimated $2.5 million per year to operate — or about $100,000 per officer — the force will require new funding once the province’s two-year, $5 million grant expires after next year; Christmas has also repeatedly suggested wanting more officers, stating a month into its operations that “I absolutely could use another 100 officers tomorrow if they were given to this.”

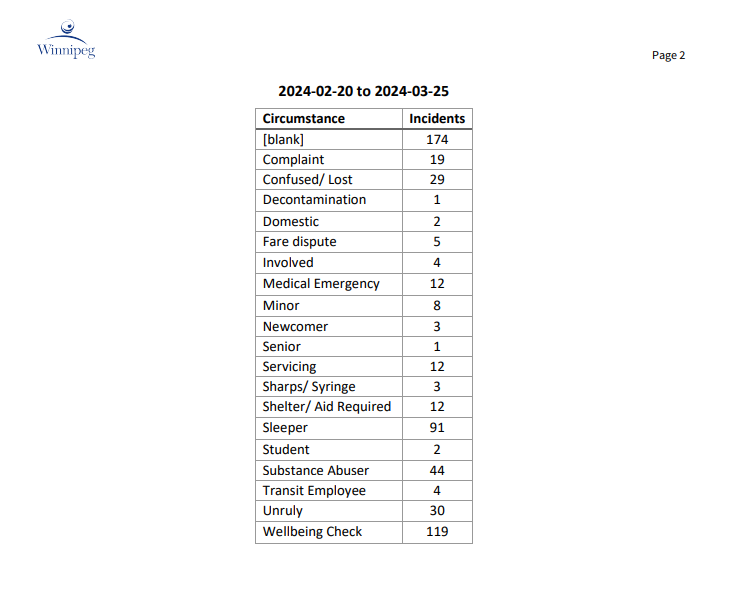

But what is the transit security force actually doing? An offhand remark by one of its two supervisors, also a former WPS officer, provided surprising clarity on the matter, admitting that a typical call in fact involves dealing with “a sleeper on the bus,” rather than the much-cited medical events. Recently obtained access to information requests from the City appear to confirm this. Unfortunately, the forces’s initial data reporting is questionable on a few fronts, including the leading incident type being “blank” and its total number of incidents not matching the City’s own reported numbers, which may be the product of multiple types being logged for a single incident. However, it still provides enough information to better understand the security force’s early priorities.

Between February 20 and March 25, the top five listed incident responses were:

- “Wellbeing check”: 119

- “Sleeper”: 91

- “Substance abuser”: 44

- “Unruly”: 30

- “Confused/lost”: 29

It’s also worth noting that, in contrast to messaging by the security force and the City itself, only 12 responses were classified as “medical emergenices.”

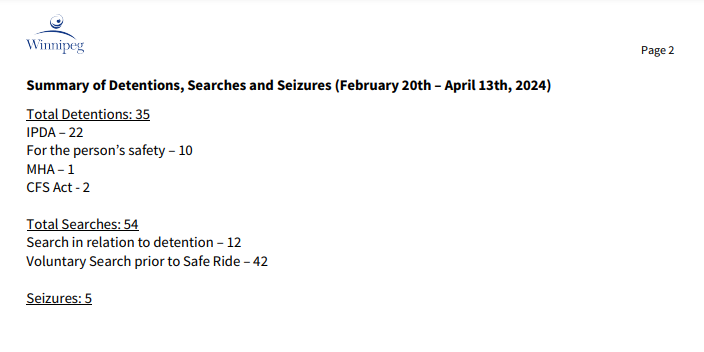

Further, between February 20 and April 13, the transit security force conducted a total of 35 detentions, including 22 under the Intoxicated Persons Detention Act (IPDA), 10 “for the person’s safety,” 2 under the Child and Family Services (CFS) Act, and 1 under the Mental Health Act (MHA). The force also searched people 54 times: a dozen times in relation to detention, and 42 times as a “voluntary search for Safe Ride,” which are provided to shuttle people to emergency shelters like Siloam Mission and Main Street Project. There were five seizures conducted as well, although it isn’t specified of what.

The language used in these disclosures is both disturbing and telling. Drug use is not only assumed but stigmatized and pathologized in “substance abuser,” while people using the bus for rest and warmth are derided as “sleepers.” The numbers and broader media reporting also suggests that the work of the security force is not to actually ensure everyone’s safety — which includes the person who is being responded to — but to rather offload people perceived to be unwell, intoxicated, unruly, or confused.

Unsurprisingly, this displacement from buses does not remedy many situations: in one highly publicized incident in mid-March, an “erratic” man was removed but “once they got him off the bus, he walked into traffic” and “the safety officers approached him again, but he then hit them and tried to bite them, according to WPS, before the officers got him into custody.” This also encompasses transporting people who aren’t even using buses to shelters, even when it doesn’t seem desired. For instance, CBC News reported in late March: “Over on Main Street, Berman and the other officers gave the woman a blanket, and offered her a ride to a nearby shelter. The woman seemed reluctant to get into the officers' vehicle, but the team continued talking, hoping to gain her trust.” The goal is clearly not to resolve issues but funnel them to the shelter system or criminal punishment bureaucracy.

There’s certainly a need for more non-police responses to crisis situations in public spaces like transit and libraries. However, with only six weeks of training and intimate ties to the WPS — including leadership by two former officers and training conducted by a former WPS chief — this new transit security force is unable to play that role. Any response that aims to actually improve safety, rather than merely displace the person and issue elsewhere, would centre provision of basic needs, peer-led harm reduction outreach, non-coercive mental health responders, and people who have the experience and disposition required to genuinely de-escalate a tense situation. So-called “wellbeing checks,” which are also the leading category of incident that the WPS respond to, cannot be successfully conducted by people who look or feel like cops. Actually helping people who are “confused/lost” doesn’t require an officer armed with a baton and handcuffs.

But more generally, it must be recognized that a response service will be utterly insufficient so long as people are systematically deprived of safe and legitimately affordable housing, healthcare, food, and infrastructure to undo the drug poisoning crisis like a safe/legal supply of drugs and safe consumption sites. Without such options, responses like the transit security force will continue to cycle people through shelters and emergency services, never actually doing anything to improve safety for anyone (especially if the person ends up being further criminalized, which will radically decrease safety). While allowing politicians to claim that they’re “doing something” and creating a handful of jobs for aspiring or former cops, the notion that two dozen officers — or even 100, as Christmas hopes for — could meaningfully create safety on transit is totally unfounded, just like the broader policing apparatus that it’s based in.