Traffic violence is a very real and understandable concern for pedestrians and cyclists in Winnipeg. In May 2025 alone, Winnipeg drivers hit and killed at least two pedestrians. They also regularly endanger cyclists, as exemplified by how drivers struck and killed cyclists in June and August 2024.

Organizers from the cycling community have been calling on the City of Winnipeg to make cycling safer by implementing bike lanes, reducing speed limits, and improving traffic signals. At the same time, some cyclists are turning to the Winnipeg Police Service (WPS) to demand greater protection. Their demands include more cops on bikes and more traffic enforcement. But in reality, policing is at odds with safety. The threat that drivers pose to cyclists and pedestrians cannot be resolved through policing.

Cops don’t keep pedestrians and cyclists safe

Ultimately, police endanger cyclists—and we can’t count on them to keep us safe. The WPS in particular has long been violent against cyclists. In 2006, the WPS repeatedly attacked Critical Mass bike rides, arresting and beating participants. They have also assaulted individual cyclists, as in 2019, when notorious cop Jeffrey Norman pepper sprayed a cyclist. Police have not been held to account for this violence, with many cops receiving small fines and short license suspensions at most. Cops also routinely threaten pedestrians, as well. As we documented after the WPS killing of Tammy Bateman—when an officer hit her while driving a cruiser at high speed through a small park at night—police constantly drive with an extreme recklessness that has killed and injured many people over the years.

The WPS regularly excuses and justifies traffic violence. In March 2023, then-police chief Danny Smyth claimed that the 28 traffic deaths in the previous year—including 12 pedestrians—could at least in part be blamed on the COVID-19 pandemic, suggesting “a lot of anxiety, there is a lot of anger out in the community and I think it manifests itself through… things like traffic.” As with all police violence, the WPS also frames their own traffic harms as outside their control, claiming the cops who hit and killed Bateman are “devastated” and “want[ing] to know what happened.” But targeting drivers shouldn't be seen as an effective solution either, given WPS traffic stops have long proven to be deadly. Putting drivers at risk of police brutality doesn't keep cyclists safer.

Police harm vulnerable road users

In addition to vehicular violence, police also threaten cyclists through routine racist surveillance and ticketing. Across the city, people cycle on sidewalks when they perceive cycling on the road to be unsafe. In areas with less cycling infrastructure, it follows that people are more likely to bike on the sidewalk, or less likely to bike altogether. There is a noticeable lack of infrastructure in areas of the city with more Indigenous, racialized, immigrant, and low-income residents.

That inequity is amplified by police, who consistently target Indigenous and racialized cyclists. For example, an Indigenous parent told researcher Fadi Ennab: “My son has four close friends…. They talked about how many times they got stopped by the police riding their bikes. My son said, ‘So many times I can’t count anymore.’ His friends also said that every time they ride their bikes, police stopped them and ask them: ‘Is this your bike?’ So, it got to the point where my son quit riding his bike to school…. If he is walking home, the police would slowly drive by him.” Ennab also cited other research about Indigenous youth in Winnipeg: “If you are on a bike in the inner city, you face a tough choice. If you bike on the street, you risk being hit, injured, or killed. If you bike on the sidewalk, you risk being detained, accused, searched, and fined. Especially if you are Indigenous … [unlike] white people [who] were biking freely all over the same sidewalks.”

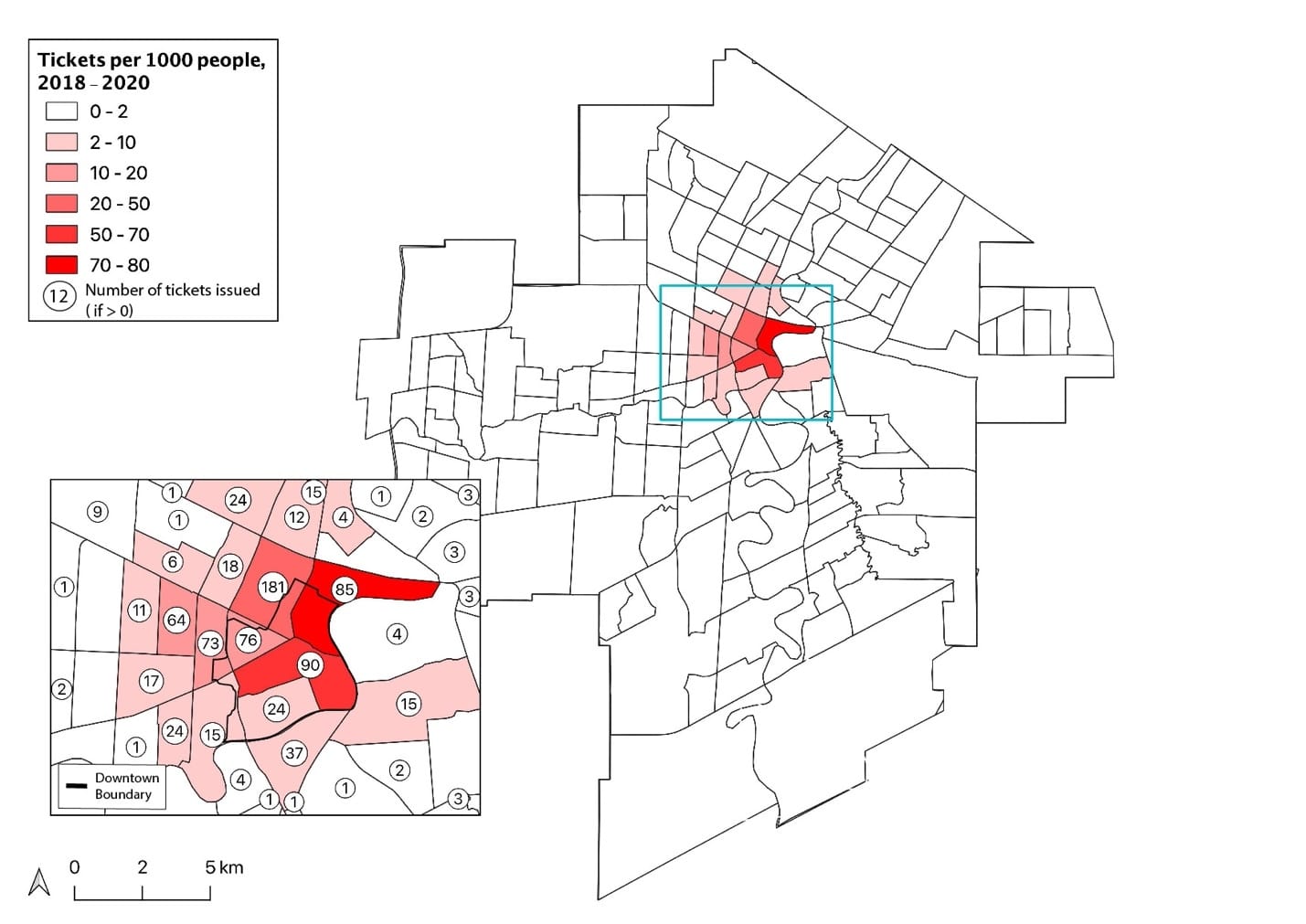

In alignment with Ennab’s study, research on the distribution of cycling tickets across Winnipeg found that tickets were most likely to be “issued in areas that generally had more racialized and immigrant residents, and uniformly had more low-income residents.” This research pointed out that citywide, between 2018 and 2020, 1 ticket was issued for every 1,000 people. However, that rate jumped to 77 tickets for every 1,000 people in inner-city areas. In total, 58% of all tickets were issued in inner-city areas, which contained only 2% of the city’s population. Crucially, ticketing did not correlate to any safety metric, proving once again that policing neither intends to make people safer nor results in safer outcomes—and especially not when there are multiple immediate solutions that the city can implement.

Infrastructure saves lives

Force—which is the only strategy police provide—can't solve the issue of traffic safety. Traffic safety is a political and infrastructural issue that requires political and infrastructural solutions, all of which are deeply intertwined with a wide range of issues including reducing emissions and air pollution, improving accessibility for people with disabilities, and cutting the often enormous costs of car-dependent mobility.

The best and most immediate way to keep cyclists safe is to establish a protected network of bike lanes and cycle tracks across the city. Separated bike lanes—using concrete barriers, not just painted lines or flimsy bollards—are essential infrastructure that make streets safer for cyclists (and sidewalks safer for pedestrians). They are needed across the city, especially in lower-income and racialized neighbourhoods where police criminalize people for riding their bikes. On June 6, community members came together to build a functional bike lane on Wellington Crescent, demonstrating that our streets are only unsafe because the City is choosing to keep them that way. In fact, rather than using their resources to make the bike lane permanent, the City deployed resources to remove it later that night.

Besides bike lanes, many other policy changes can easily and dramatically improve safety for pedestrians and cyclists. One such measure comprises reducing speeds to 30 km/h anywhere that vehicles may hit pedestrians and cyclists; Vision Zero Canada notes that “when the crash impact speed rises from 30 km/h to 50 km/h, the fatality risk to a pedestrian increases five to eight times.” Countless other “traffic calming” strategies can further reduce threats, including narrower lanes, corner radiuses, pinch points, raised crosswalks, speed humps, and pedestrian refuge islands. Intersections also require pedestrian and cyclist priority signalling, good lighting, and better signage.

Car-free zones and pedestrian streets increase the number of spaces that people can access without worrying about cars. They can also become important community spaces and have been successfully implemented in a number of cities, including Montreal, which now has at least eight pedestrian major streets throughout the whole summer. Paris recently voted to make another 500 streets car-free and pedestrianized, adding to the more than 200 that already existed. Winnipeg’s upcoming pilot project on Graham Avenue is a promising start—but should be made permanent and greatly expanded in number. At the same time, governments must ensure public transit services are frequent, reliable, and affordable to get people out of cars altogether.

Getting cops out of traffic enforcement

While it may feel counterintuitive to some, calling for less police involvement in traffic safety is an essential component of road safety. If we truly desire safer roads for all, then we need infrastructural and cultural shifts, not policing. At best, police can “punish” drivers for violating traffic laws, and they often do so highly unequally. With that also comes police “punishing” cyclists, and police using the opportunity to profile, surveil, and criminalize people using the roads.

We shouldn’t pretend that subjecting people to police violence makes cyclists safer, especially not when we can improve traffic safety so many other, better ways. Traffic safety can and should be led by a civilian department instead of police: one that has the expertise, training, and mandate to reduce traffic violence rather than simply exploit it as a revenue-generation strategy.

The city must also broadly restructure its approach to mobility, and incentivize people to use transit, bikes, sidewalks, and more. Issues that can deter many people from cycling, such as bike theft, can be best addressed through improving bike parking and storage, distributing higher-quality locks, and educating riders on best locking practices. Bike theft, like all petty theft, can also be prevented by changing the material conditions that force people to steal to survive.

Police have no role in cycling safety. They threaten cyclists and pedestrians from their cars, and they threaten marginalized drivers and cyclists through racist profiling and violent actions. To make cycling safer, we need to call on the city to invest in proven strategies and to divest from harmful ones.

Right now, bike activists are leading a targeted campaign for safer speeds and a protected bike lane on Wellington Crescent. One way to get involved in this struggle is to contact public works committee chair Janice Lukes (204-986-6824 or jlukes@winnipeg.ca) to express your outrage at how she recently suppressed democratic public participation, along with how she has repeatedly refused to fast-track safer speeds and infrastructure measures on the dangerous street.

More broadly, we encourage everyone to critically reflect on and problematize the role of police in traffic safety. While some may feel safer in the presence of cops, many do not, and will avoid involving police in dangerous situations. We must not revert to fanciful beliefs in the possibility of “police reforms”. Instead, we need to focus on defunding and de-tasking the police, and reallocating their enormous budgets to services and infrastructures that actually keep pedestrians and cyclists safe.