The negative connotation attached to protesting in the dominant discourse today is due to the recent occupation of the “Freedom Convoy” in Canada, which has expanded to the United States, New Zealand, Australia, and France.

In Winnipeg, the “Freedom Convoy” occupied public streets in front of the Manitoba Legislature for three weeks. Those opposing the vaccine mandates were continuously causing disruption, resulting in perturbation and distress to many downtown residents.

During the occupation and after its departure, people are criticizing the inadequate response of the Winnipeg Police Service (WPS) to the noise and harassment complaints that residents reported throughout the convoy occupation. Community members at the recent police board meeting on March 4th condemned WPS for its poor handling and for “catering to the occupiers.” Last month, even Mayor Brian Bowman expressed discontent and disappointment with the police’s handling of the protestors, calling it an “unlawful occupation” whose presence was dangerous to the public.

With the growing dissatisfaction with the police’s response to the recent “Freedom Convoy,” we ask: are the police truly "impartial" during public demonstrations?

Quick to respond to criticism of the police’s management of the “Freedom Convoy,” WPS recently established a Substack account wherein they attempt to explain the various tactics and techniques used in police intervention during “large-scale gatherings.” Danny Smyth, chief of WPS, authored a post entitled: “The Rising Trend of Protests and Marches – Thou Doth Protest Too Much,” wherein he refers to these spaces of contestation as sites of police interest.

Smyth writes that:

Yet, the past month has shown the police’s indifference to the “Freedom Convoy." Despite this promise of impartiality, there is a clear difference between how the police treated the “Freedom Convoy” occupiers who are predominantly White and affluent and how they interact(ed) with racialized and marginalized people, particularly Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour.

It is unfortunately unsurprising to many that the only people arrested at the illegal convoy occupation are two Indigenous counter-protestors. Grand Chief Jerry Daniels of the Southern Chiefs’ Organization points out how “it’s really hard to see how these two individuals could have been having a more negative impact on society at the time of their arrest” compared to the occupiers disrupting downtown Winnipeg in February.

Furthermore, more peaceful public demonstrations were interrupted by WPS in the past. During the 2008 International Day Against Police Brutality rally, WPS, including Smyth, confronted and threatened an Indigenous protestor using verbal aggression. In 2006, cops arrested Critical Mass Winnipeg protestors using excessive force and charged them for assault. These are examples of biased police intervention in public demonstrations, but their blatant use of force and violence in their everyday duties must be noted as well.

Why are the police uniquely empowered to arbitrarily inflict violence? How is it that they employ more severe techniques when interacting with Indigenous peoples, Black people, People of Colour, people who are living with mental illnesses, people who are homeless, and people with substance use disorder?

The argument being made here is not that Winnipeg Police Service should have used the same violent techniques and tactics they use on marginalized and racialized communities on the convoy occupiers, but rather, that we should be challenging how the police wield “incredible power and authority” over the community’s safety and security.

The police are only unwelcoming to public dissent when said dissent comes from marginalized communities. When the “protestors” are dominantly White and affluent, their “civility” while protesting is exemplified and applauded by the police. How can the police frame the convoy occupiers as “cooperative and peaceful” despite their illegal and unlawful occupation? The convoy organizers’ ability to liaise with the Winnipeg Police Service is also redolent of their privilege.

In a separate post on the WPS Substack, Dave Dalal, Superintendent Uniform Operations, explains that the “police services continually learn and improve their policies, training, and tactics to maintain public order and ensure public safety” during large-scale gatherings. But who are they keeping safe? Who were they keeping safe at the “Freedom Convoy”?

Contradicting Smyth and Dalal’s argument, police intervention at protests, marches, and rallies was never impartial nor geared towards real public safety for all those concerned, especially when these spaces involve racialized and marginalized communities actively intervening in state repression.

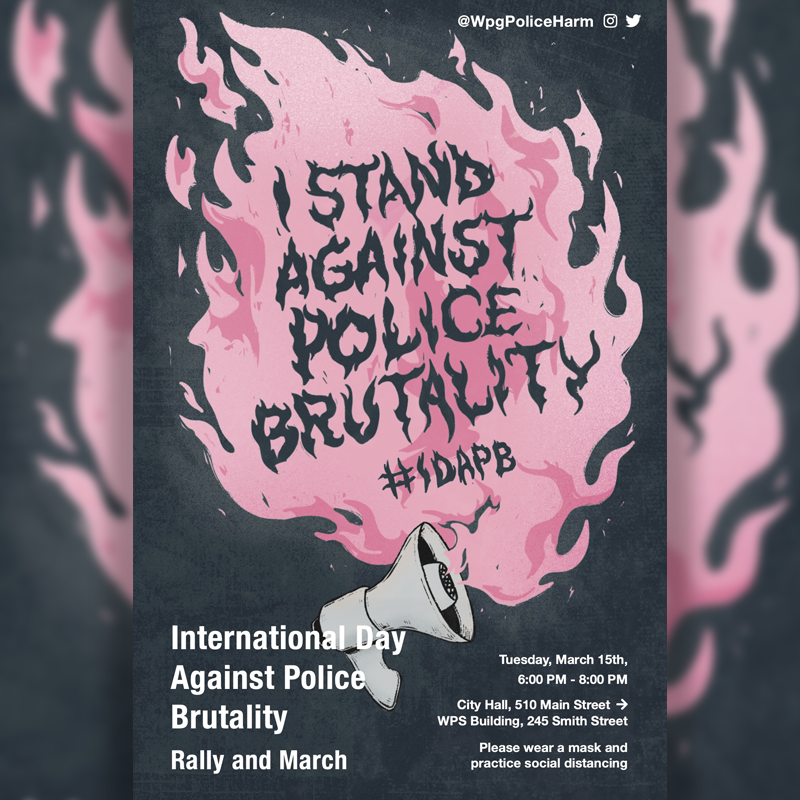

As we once again protest in solidarity against police violence on International Day Against Police Brutality on March 15th, we must continue to question the ways in which police are present to “maintain public order and ensure public safety” in spaces that do not initially require their protection – most importantly community spaces, such as schools, parks, and libraries. Moreover, their everyday practice of exploiting state power through means of violence in their regular duties must constantly remind us why we should “protest too much.”