Winnipeg’s budget season is upon us once again, with the preliminary budget to be released on Feb. 7. This year’s process is arguably the most important in some time, as it’s the development of what’s called the “multi-year budget,” which will cover the next four years: from 2024 to 2027. While individual budgets can and will be minorly tweaked within this span, the multi-year budget sets the broad trajectory and framework for the years to come.

As a result, it’s more important than ever to pay attention to this budget season, and join in with many others who are demanding a divestment from policing and jailing, and a reallocation of resources to life-sustaining services like public housing, safe consumption sites, food security programs, libraries, community grants, and much more. A few key ways that you can get involved are presenting to council (either in-person or over Zoom), speaking with your councillor (in the form of a meeting, phone call, or email), and helping spread the word to others.

However, budgets and the surrounding processes are very bureaucratic, confusing, and daunting. Mayor and council constantly obscure their own powers and responsibilities, blaming other city committees or levels of government for their own inaction. As we enter the multi-year budget season, here are four key facts about WPS funding to keep in mind this budget season.

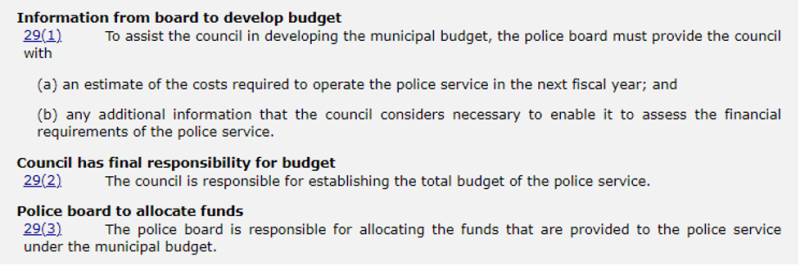

1. City council, not the police board, determines the WPS budget

Every year, politicians and the media implicitly (and sometimes explicitly) trot out the same phony narrative that it’s the police board — the city’s supposedly arm-length civilian oversight body — that determines the annual police budget. Given that the police board develops its budget recommendation on the basis of the police’s own submission of what it thinks it deserves, this notion more-or-less implies that the cops get to decide their own budget.

This couldn’t be further from the truth. As made very clear in the provincial Police Services Act, which is the legislation that governs all policing in the province, the police board is only tasked with providing council with “an estimate of the costs required to operate the police service in the next fiscal year” and “allocating the funds that are provided to the police service under the municipal budget.” Yet it is council that has “final responsibility” for the budget.

Here’s how the police board itself explains the process on its website: “The Board may therefore recommend maintaining or investing in the Winnipeg Police Service, based on the goals of its strategic plan. Council, on the other hand, considers additional factors when it sets the municipal budget. It may choose to increase investment in the Service, use investment in other areas to promote public safety, or balance the funding needs of the Winnipeg Police Service with municipal budget constraints. If Council sets the Winnipeg Police Service budget at an amount that is higher or lower than the Board's recommended estimate, the Board works with the amount set by Council to allocate within the Service.”

Anybody who claims that it’s the police board’s responsibility to set the budget is either ignorant of the governing legislation and stated process, or lying to you.

2. There’s no minimum requirement of cops in Winnipeg

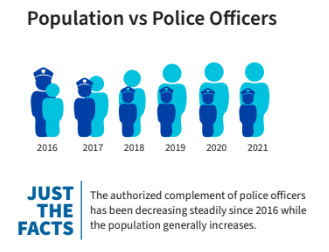

One of the police’s favourite propaganda tools is to incessantly point out the declining per-capita ratio of sworn officers to civilians in the city. This tactic has become increasingly absurd in recent years, including the force’s annual report in 2021 including a comically disingenuous and data-free graphic, as seen below.

While Winnipeg’s police-to-civilian ratio has indeed been falling for a decade — as in the case in many places due to growing populations and ongoing “civilianization” of policing — Winnipeg’s ratio still remains well above other large cities including Toronto, Calgary, and Ottawa. Yet something left unspoken in many of these debates is that even if Winnipeg’s ratio was uniquely out of sync with comparable municipalities, there’s no legislated requirement that it be any higher.

The sole definition of police requirements in Manitoba is that policing is “adequate and effective.” It is an entirely subjective metric without any linkage to minimum numbers or ratios. A recent review of the provincial Police Services Act that was conducted by a cop-stacked non-profit pointed out this discrepancy, noting that “nowhere in Manitoba’s legislation or regulations is ‘adequate and effective policing’ defined.” Yet this glaring issue wasn’t addressed in the series of amendments made by the last provincial government to the legislation.

This means that regardless of what the cops and their union claim, there is in fact no necessity for the city to fund them at any specific level. The only threat is that the province could step in and claim that funding levels aren’t sufficient to ensure “adequate and effective” policing, but this would require the newly elected NDP to burn significant political capital in the process. Constant appeals to declining ratios are merely a desperate technique by greedy, self-interested police to extract ever-more money from the public. They should be totally ignored.

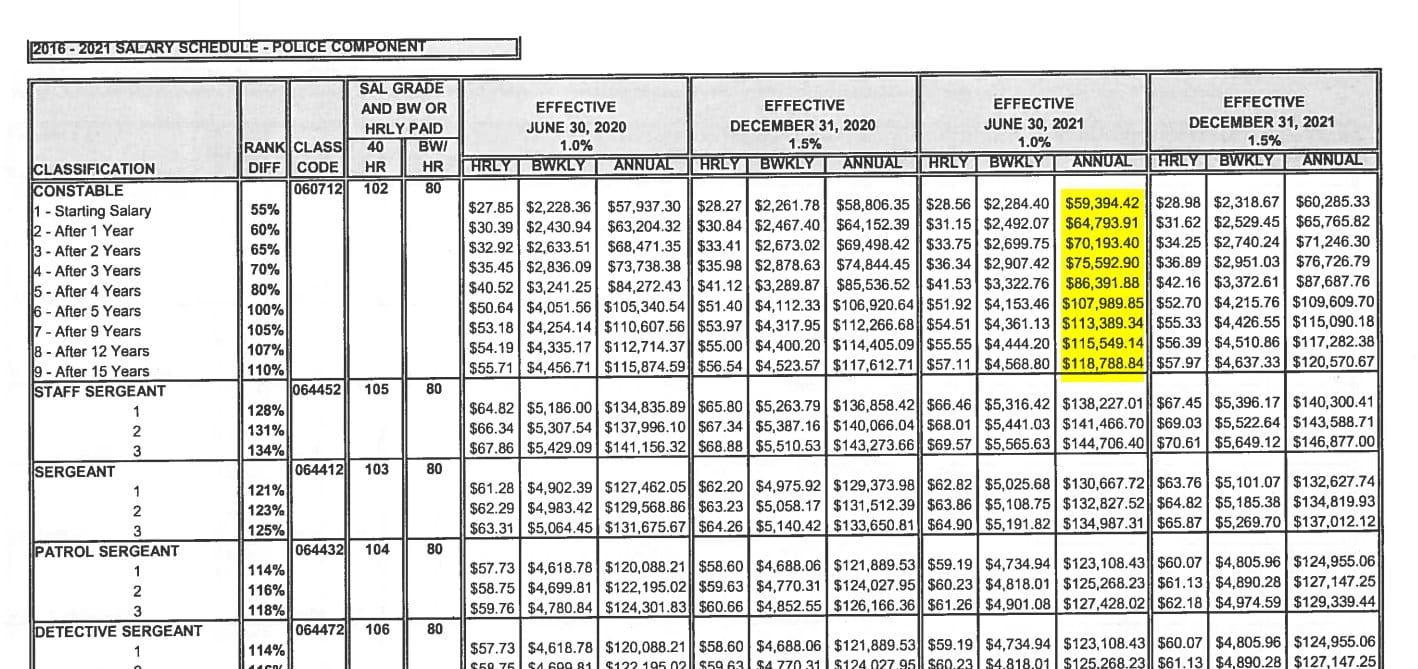

3. All budget increases will go to paying ever-larger salaries to the same number of cops

Closely related to the above issue is that the ever-increasing police budget is being poured into the constantly rising salaries, benefits, and pensions of roughly 1,500 cops, at least one-fifth of whom don’t even live in the city (and thus pay lower property taxes to neighbouring municipalities). The WPS could hypothetically be hiring many more officers at lower pay if the police union allowed for it: the biggest limitation is the massive compensation that cops receive, meaning that the police-to-civilian ratio will inevitably fall with a growing population.

In 2022, almost 1,300 WPS employees made more than $100,000 a year (compare than to 60 for Winnipeg Transit and 23 for all of Community Services). In total, 52 of the 100 highest-paid city employees were cops; in contrast, the departments of community services and public transit only had one employee each in the top 100. A cop starts making a six-figure salary after only five years on the job, seeing an 80 percent pay rise in that period alone.

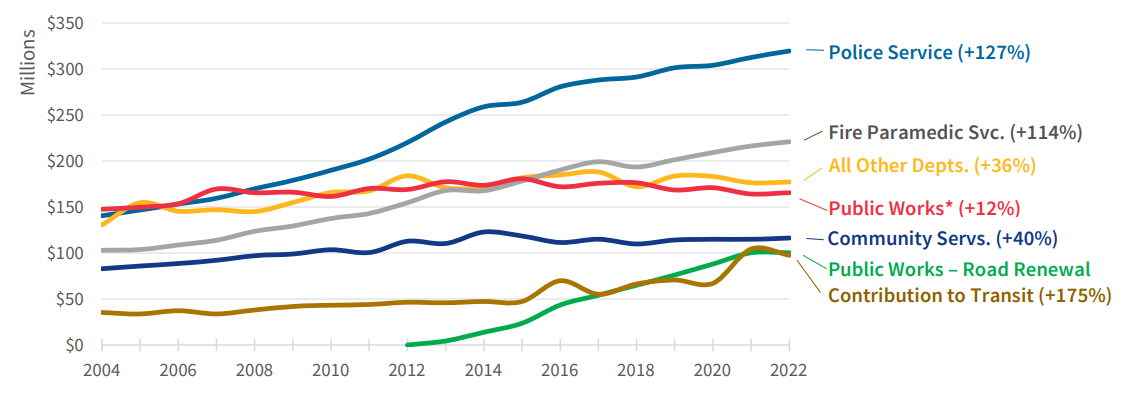

While there are many other obvious manifestations of police greed (think of expensive toys like the helicopter and robot dog, or district stations that they refuse to open to the public), these salaries, benefits, and pensions are at the heart of the police budget crisis in Winnipeg. It’s in large part because of this trajectory that the police share of the city’s operating budget has spiked from under 17 percent in 2000 to well over 25 percent in recent years.

And this problem will only get much worse in the coming years, with city funding of police skyrocketing to more than $300 million a year (and the total WPS budget upwards of $350 million) by only 2026 or 2027, absent a very serious overhaul of the budget.

4. The collective bargaining agreement does not dictate the budget

Along with deceptively deferring responsibility of the WPS budget to the police board, one of council’s favourite tricks is to claim that they ultimately have no power because compensation and other costs are negotiated through the collective bargaining process; we can look to former mayor Brian Bowman’s failed attempt to unilaterally impose a rebalancing of the pension formula outside of the collective bargaining process as a clear example of what they are hinting at with this.

Yet the budget-making process is not specifically bound by the collective agreement. Of course, estimates of compensation costs will be dependent on negotiated increases. However, these increases only apply to employees that the city provides sufficient funding for. Union contracts have had no bearing on the decision of the city to cut funding to other city services, because specific negotiations over wage schedules are not relevant to such determinations.

City council can certainly slash the police budget and require the WPS and police board to figure out how to cope with the reduced funding, including through mass layoffs, a hiring freeze, overtime ban, and attrition. The cops are well aware of this reality, too, having successfully appealed for funding top-ups above their already huge budget as “layoffs would exacerbate the use of overtime, further impact the health and wellness of members and have a detrimental impact on service delivery.”

The facts are clear: the city can defund the WPS and reallocate its enormous budget to life-sustaining services that actually keep people safe. The real challenge is building a collective struggle that is powerful enough to force city council — as well as the province, which funds the WPS to the tune of $20 million a year — to concede to our demands for real safety in Winnipeg.