After years of threats, Winnipeg is finally creating a dedicated transit security force, using $5 million in provincial funding “to implement safety and security measures” in its new 2023 proposed budget.

The general idea of transit security is by no means new to Winnipeg. Transit supervisors, who are former bus drivers tasked with enforcing the Public Transit By-Law, have existed for more than a decade. In recent years, both police officers and cadets have started patrolling buses and transit corridors with far greater frequency, including a massive and inexplicable increase of cops on buses during the early years of the COVID-19 pandemic (the police union has been in a protracted turf war over who should be responsible for transit safety, claiming that it should be police work while also constantly complaining about being chronically overworked).

Specifics on the new transit security force remain scarce. Mayor Scott Gillingham, who campaigned on introducing such a force, is working hard to downplay the change by terming it a “‘transit security team” that is unarmed and collaborating with existing organizations “to make sure that the individuals get the services they need.”

This approach implicitly echoes the ethos of security networks like the Downtown Community Safety Partnership (DCSP), a supposedly less harmful response that nevertheless “serves to shore up the private interests of capital in downtown Winnipeg,” particularly True North Sports & Entertainment (True North developed the idea of the DCSP, chairs the board, and has its former head of security — before that a WPS officer — as the DCSP’s executive director).

However, the transit union — which has pushed for transit security for years — wants far more than an unarmed team focusing on de-escalation: it is calling for them to carry Tasers, pepper spray, and the power to detain and arrest (which is almost the exact description of the province’s new class of police-trained “institutional safety officers” being rolled out in hospitals and universities). Given Gillingham’s willingness to install police in Millennium Library and contract notorious private security giant GardaWorld to perform a “safety audit” of the building, there’s little reason to think he won’t seriously contemplate such options.

Transit safety is a very real issue in Winnipeg. Bus drivers have been stabbed to death, attacked with bear spray, forced to escape out windows, and punched in the face. Riders have also faced considerable violence in recent months, including being attacked with a machete and physically and sexually assaulted at a bus shelter. There has also been media coverage of incidents that haven’t culminated in violence but have still left riders feeling threatened and unsafe.

These situations cannot be minimized or brushed aside. In addition to the acute impacts of violence, they are undoubtedly contributing to riders and drivers abandoning transit altogether. Violence on transit is a major workplace safety issue and the union is obviously right to be deeply concerned about it.

However, transit security is not the answer. Rather, it is crass “security theatre” that will do nothing to confront the underlying crises manifesting in these spaces. Worse still, it will actively undermine transit access for the people who need it most, while wasting money that could otherwise be funding real solutions to this extremely serious problem. If we actually want real transit safety, we can’t afford to get distracted with carceral fictions and must stay focused on evidence-based policy that reduces the factors contributing to violence in the first place.

Here are five main reasons that transit security isn't the answer to safety issues in Winnipeg.

1. Transit is too large to effectively monitor

In the continued push for a transit security force, the union local has pointed to several recent examples of violence as evidence for why such a response is necessary.

One was the vicious attack of an 18-year-old woman at Chancellor Drive near the University of Manitoba; the local president said about the security force that “hopefully the announcement today … will give her the comfort of being able to come back to a safe transit system.” Another was the aforementioned machete attack, with the local president suggesting that the presence of transit security may have deterred the attacker from boarding the bus in the first place.

These are both incredibly scary situations. But the notion that security would have stopped them is deeply naive. In both cases, the attacks didn’t happen on buses, but one at a bus stop and the other after getting off the bus. There’s almost no reason at all to believe that a transit security member would have been in the vicinity and capable of intervening in either of these attacks; the concealed machete could have only been noticed if every rider was subjected to a pat-down and metal detection screening, a clearly farcical proposal.

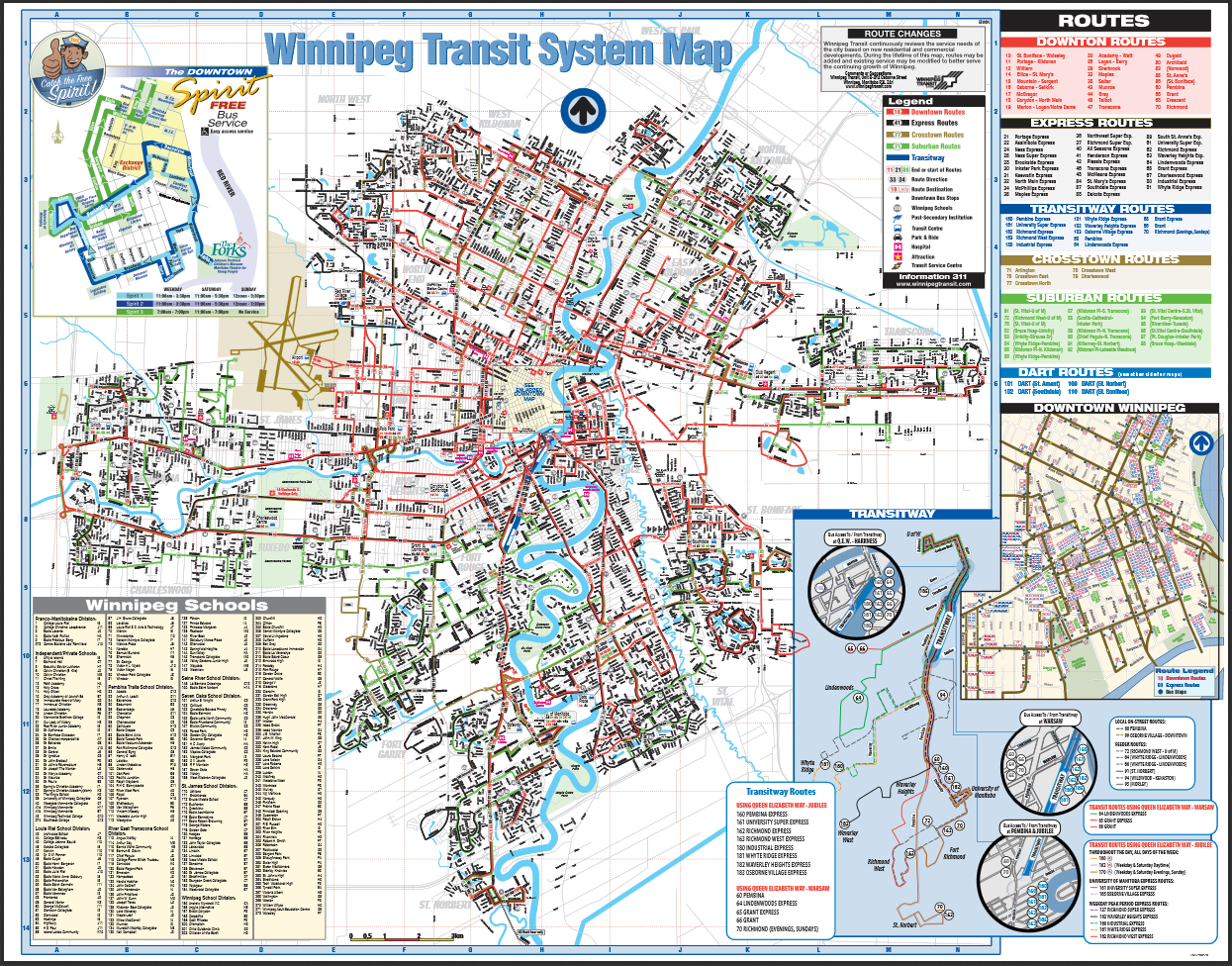

There are 87 bus routes, 870 bus shelters, and 5,170 bus stops in Winnipeg. Busy routes often start service shortly after 5 am and continue until after 2 am. In total, Winnipeg Transit buses operated for over 1.5 million hours in 2018. While far smaller than transit systems like those of Toronto or Vancouver, it’s still an enormous network of service and infrastructure.

The objective is presumably to prevent harm, not simply to respond to it after it occurs. Transit security would have to be able to cover every possible location of transit operations, especially less-visible locations where attacks are more likely to occur. For example, driver Irving Fraser was killed in 2017 at the end of a route, just before 2 am, by the sole remaining passenger on board, while the aforementioned attack on an 18-year-old woman happened at 10 pm while waiting for a transfer.

For transit security to have such an intensely comprehensive scope, there would have to be many hundreds — if not thousands — of personnel on buses and at or around bus stops almost around the clock. This would require a truly mammoth expansion, with total hiring likely exceeding the number of bus drivers. A $5 million force will barely scratch the surface.

2. Transit security doesn’t “deter” violence

Then there’s the much bigger issue: even if transit security are around, there is little reason to think that it will deter violence. We know that this is true of policing more generally: after all, if policing “deterred” violence, then Winnipeg’s $324 million police force would mean that the city was the safest that it’s ever been.

Simply put, people in conditions where violence is being considered or deployed — whether it’s robbery for money to buy things needed to survive, or a “random” lashing out to a combination of factors such as trauma, toxic and unregulated drug supply, or untreated mental health issues — are not likely to care too much whether there are police or security in the vicinity.

As argued in a 2016 article examining claims of police (and even the threat of the death penalty) deterring crime: “when a person is desperate, they’re not usually considering sentencing guidelines. They know what they’re doing is illegal, but that’s about it. Their desperation is the most important thing.”

Their desperation is the most important thing.

For instance, Toronto recently assigned 80 cops to patrol the TTC due to a recent string of violent incidents. In the days following the announcement, there were at least four serious attacks including two robberies and two assaults, including one in which three people were assaulted on a streetcar “minutes east of city hall.”

The same has played out on a more limited scope in Winnipeg with its transit supervisor and inspector personnel. Despite playing a quasi-security role, these personnel are frequently attacked, leading to the city recently spending $65,000 on equipping them with slash-resistant vests. Their presence not only fails to deter violence — they’re often the targets of it.

Even if someone does conduct a cost-benefit analysis and opt to relocate an attack or robbery to another, less visible locale, this hasn’t deterred violence, but merely relocated it. About the Toronto situation, NDP MPP Jessica Bell noted: “So, a police officer will move an aggressive person from the TTC onto the street? Then what? Does it become a problem for pedestrians?”

The notion that a transit security force will magically alter this trend is a comforting fiction that simply has no basis in reality.

3. Transit security disproportionately targets poor/racialized riders

Police and security may be ineffective at preventing violence and harm on transit. But they are extremely effective at harassing, displacing, and otherwise harming poor and racialized transit riders.

There is widespread documentation of the relationship between securitization and vastly disproportionate targeting of racialized riders. Tickets for fare evasion are the most visible manifestation of this trend, with Indigenous riders in Edmonton receiving almost half of all tickets since 2009 (Indigenous people only make up 6% of the population) and Black riders in Toronto receiving 19.2% of tickets between 2008 and 2018, a two-fold overrepresentation.

Then there are the killings and assaults. Vancouver’s dedicated transit police force have a long track record of violence against Indigenous and racialized people including the 2013 arrest of Lucía Vega Jiménez, an undocumented hotel worker who later hanged herself while awaiting deportation, and the killing of Naverone Woods in 2014. In April 2021, a Black woman was pinned to the ground, punched, and put in an attempted chokehold by Montreal transit inspectors. In Winnipeg, Michael Bagot died from a heart attack in 2019 after Winnipeg Police arrested him while he was in a “drug-induced state” on a Winnipeg Transit bus.

None of this is surprising given more general trends of policing and security. Indigenous and Black people are vastly overrepresented in police response and charges, while Indigenous people in Winnipeg are frequently subjected to racial profiling in Superstores, Shoppers Drug Marts, and even parking lots. These trends are constant and systemic. And while a transit security force may be presented as an alternative to police, it is certain that they will work in close collaboration with police.

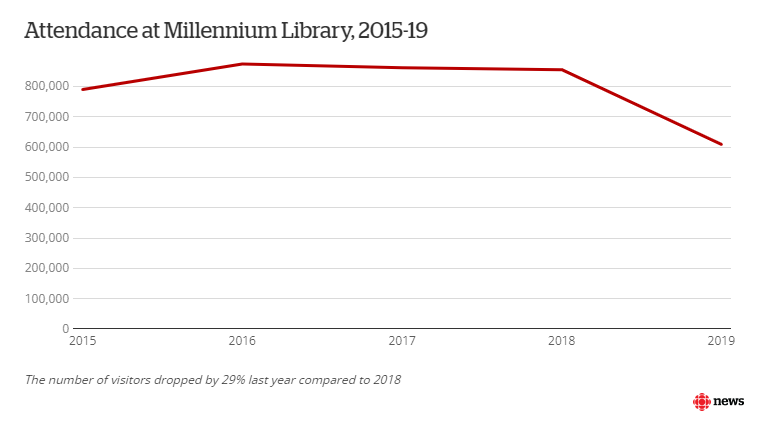

If transit security has any deterrence effect, it may well be that of deterring poor racialized riders from using transit due to risk of such harassment or violence (rather than deterring other kinds of violence from occurring). Although a clearly different situation, such an impact was noticeable after the installation of the first round of security screenings at Millennium Library in early 2019, resulting in 250,000 fewer visits.

A big part of this also has to do with the kind of transit system that a city wants to build. As Christof Spieler argues, this goes beyond — but obviously includes — the use of police and security as “transit systems have racism built into their schedules, their fleets, their route structures and their infrastructure.”

For example, in Winnipeg, a huge chunk of transit funding is going into the Southwest Transitway, which primarily services university students, sports fans, and more affluent suburban residents (it also benefits private developers building “transit-oriented development” along the route).

While undeniably positive infrastructure, it has to be understood in the context of simultaneously underfunding bus service in the North End, as well as the cancellation of the free Downtown Spirit in 2020. There is a certain class of rider that Winnipeg wants to use transit — white, affluent, “choice” riders who can afford to pay ever-increasing fares — and security fits exactly into that objective. This can also be seen in the ceaseless war on the unhoused, including the city’s systematic destruction of bus shelters to impede their use as shelter in the cold.

As Toronto outreach worker Lorraine Lam recently put it in a forum on transit safety: “Whose safety are we talking about? What is safety? Who's the public that we're talking about? And where do people go?” The same questions must be asked in Winnipeg, especially given everything we know about the undermining of safety caused by transit police and security for racialized riders.

4. Transit security wastes money that could improve service

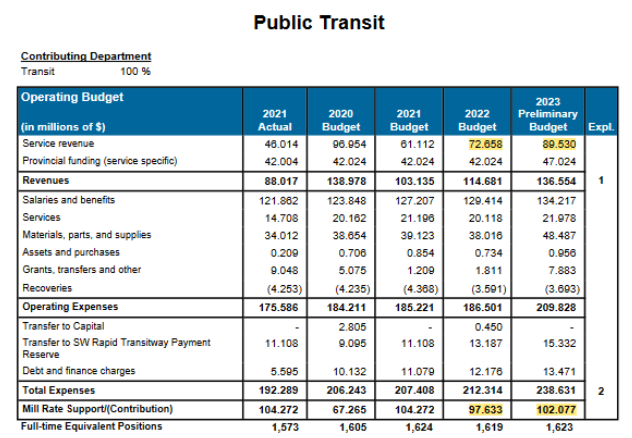

Relatively speaking, $5 million in funding to establish a transit security force is a drop in the bucket, given the city’s total tax-supported operating budget will near $1.3 billion in 2023. However, there are a few key pieces of context necessary to understand its significance.

The first is that this $5 million from the province is the first time the PCs have increased transit funding to Winnipeg since it ended and froze a long-standing transit funding agreement with the city back in 2017). This slot neatly into the recent entrenchment of a racist “tough on crime” agenda by the Manitoba PCs, including cozying up to the Winnipeg Police Association, reviving an apprehension unit, and calling for harsher federal bail laws.

There is no reason to believe the Manitoba PCs are allocating this funding in the long-term interests of public transit, a service that they have undercut for years. This is solely about bolstering their “tough on crime” credentials for the upcoming election. Unfortunately, many are falling for this gambit (there is also no clarity on the future funding of this security force).

Another related factor is comparing this funding to the budget proposal for actual transit operations. Despite consecutive years of lower than expected ridership and fare revenue, requiring significant backfilling by the city, the proposed budget is banking on ridership somehow rebounding and resulting in an additional $15.6 million in revenue in 2023. This prospect is dubious, at best, given the continued underfunding of transit service.

Yet the city is only planning to increase its upfront share for operating funding by an additional $4.4 million, less than the amount that will be spent on a security force and not even enough to cover the almost $10 million in projected fuel costs.

The only thing that will actually increase transit ridership is by making it better and more affordable (preferably free). Specifically, the goal must be to greatly improve its frequency, reliability, coverage, and comfort. Doing so will not only have numerous benefits including lower greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution, less congestion, more accessibility for people with disabilities, and greater safety for pedestrians and cyclists: it will also make transit safer.

As argued in this recent viral Twitter thread, lack of transit frequency and reliability puts people at risk of danger and exposes them to harms that they could otherwise avoid. Many attacks happen at times and places where there aren’t many other people around. By making transit good and viable, it will also ensure that people can look out for each other’s safety. This isn’t a silver bullet solution, but it’s a meaningful contribution to reducing potential harm.

We also know that fare disputes are one of the leading causes, if not the leading cause, of attacks on drivers. Saskatoon’s transit union president recently estimated that a staggering “90 per cent of our assaults are over fare disputes.” Rather than requiring bus drivers to monitor and enforce fare payment, it would make far more sense to reduce or even abolish transit fares by having transit fully funded by all three levels of government as a genuinely public service.

As transit rider Brian Gordon recently suggested to CBC: "Heck, if the City of Winnipeg decides to introduce, say, reduced or even free transit like some other cities have, you also reduce a lot of those problems, as well. More people on it, more people taking it, less confrontation with the bus drivers, with the people who can't afford it ... a little bit of safety in numbers."

Of course, $5 million would not even begin to cover such a cost. However, every dollar put towards security is a dollar that can’t be used for alternative purposes such as improving service or making it more affordable. The problem with the $5 million funding is that it’s representative of a broader tendency toward using police and security to repress and criminalize crises that would be far more effectively addressed by attending to their root causes.

5. Transit security distracts from the social and political nature of this crisis

To be sure, these root causes go well beyond a single bus or station, or even a transit system as a whole. In fact, focusing too much on transit itself can lead to a dangerous exceptionalism and result in hyper-specific “solutions” that merely displace the social contributors to violence.

This same thing can be seen playing out at the Millennium Library in the wake of the tragic killing of Tyree Cayer. While the killing objectively occurred in the library, it’s also clear that it could have easily happened in literally any public space; if security screening had stopped the chase into the library, the conflict would have almost certainly continued elsewhere.

Nothing about the library, or transit, specifically enables violence: the issue is that profound social crises are manifesting in public space where they impact many other people. Things like staffing levels and service provision can greatly help, of course, but they can only do so much.

Kyle Owens of Functional Transit put it perfectly to CBC: “Transit isn't the storm. Transit is the weather vane telling us there's a problem. I think that we're seeing the results of years of cuts of services and social supports, where so many people who are so vulnerable for so long … have lost the things that were helping them function and stay in society safely."

Transit isn't the storm. Transit is the weather vane.

The storm in question isn’t individual acts of violence. It’s austerity, poverty, colonialism, criminalization, and lack of life-sustaining services like public housing, safe consumption sites and safe supply, healthcare (including for mental health and substance use), food security, decent unionized work with a living wage, income supports, community services, and so much more. The horrific outcomes that are playing out on buses are an inevitable outcome of a society premised on capitalist exploitation, colonial dispossession, mass privatization, and racist criminalization that traps people in cycles of incarceration.

These are the crises propelling violence on transit and in other public spaces, and such violence cannot be solved without confronting their social and political roots.

To their credit, the transit union has been consistent with their “call for the provincial and federal governments to provide better resources to help those suffering from mental health, addictions, and/or homelessness. We really need to deal with the root causes while also making sure people are safe.” This is unquestionably true. However, transit security will get us no closer to any of this. Instead, it will further entrench a reactionary and carceral response to violence, wasting resources on an enticing but ultimately illusory fiction that only worsens the situation.

The only way to truly create safety on transit — and in Winnipeg more broadly — is to ensure that everyone is housed, fed, and cared for, requiring an enormous defunding from criminalization and refunding of public services and infrastructures, along with reparations and return of land to Indigenous peoples. Such a struggle will be a great deal more difficult than securing a $5 million grant for security from a cop-loving provincial government, but there’s no other option if we genuinely care about real community safety.