Progress transpires in fits and starts, and it can be dizzying to watch as important victories are clawed back by the forces of reaction. In the case of the movement for police-free schools, Winnipeg has seen important wins, with two of its six school divisions choosing to end their School Resource Officer (SRO) programs after a city-wide effort to publicize a long record of racist practices and outcomes. While the end of these two programs in 2021 immediately meant that fewer students would feel menaced by an armed police presence in their school hallways, these were incomplete wins—not least of all because there are four divisions in the city whose boards and administrators appear blissfully unperturbed by the well-documented harms transpiring in their own hallways.

In Winnipeg School Division (WSD), the largest and most diverse in the city, trustees chose to defund the program on strictly budgetary grounds, conceding nothing to the year of passionate testimony and damning research that preceded their decision. Put simply, this leaves the door wide open to police involvement with a different funding structure. The movement for police-free schools is equally a movement for robustly funded, fully public, and assertively anti-racist education, and without these further assurances, it can’t succeed. Police swarm scenes of austerity, and their soaring budgets typically complement shortfalls of social services and public resources.

Since the end of the SRO programs in Winnipeg and Louis Riel School Divisions, many forces have attempted to help police re-infiltrate these schools. Most recently, Premier Wab Kinew urged trustees to consider reinstating their SRO programs, adding that this was not a direct order from his higher office. This provocation follows a widely reported sword attack on a student at a Brandon high school earlier this month, but Kinew's use of this traumatic incident to advance a longer pro-police agenda is suspicious.

In fact, the Premier is well aware of the enormous literature and survivor accounts that recommend against his retrograde enthusiasm for policing students. Not only has Kinew himself previously voiced concerns about the long-term outcomes of such programs, albeit with an emphasis on the United States, but many members of his supposedly progressive cabinet publicly courted the high-profile demonstrations against police brutality during the tumult of 2020, as well as subsequent campaigns. Today, we can measure our distance from that movement summer by the rightward flight of those sitting politicians who stood briefly in our midst. But as Kinew proposes to reverse a positive result of that public reckoning, it’s clear that there are lessons to be learned and recalled from this work in the present.

Police-free schools in Winnipeg

Beginning in September 2020, a group of teachers, parents, students, and community members set out to document how Winnipeg Police Service’s SRO program impacted youth throughout the city. This program, beginning in the North End, placed eighteen armed police officers in more than one hundred Winnipeg schools on a rotating basis, with virtually no oversight and a dangerously ill-defined mandate to “build relationships.” First-hand testimonials were collected through a website and campaign called Police-Free Schools Winnipeg, formed amid a continental movement against police brutality and racism, and following the local standard raised by groups like Justice 4 Black Lives and the family of Eisha Hudson, killed by Winnipeg police at the age of sixteen. This was delicate work, where many of the teachers involved had already been disciplined or threatened in their workplaces by administrators for flagging the problematic behaviour of their SROs, or for sharing content on social media that was deemed unsuitably critical of police.

The prejudicial practices of police in schools were widely observed, and the harmful effects of these programs well-researched and understood, long before this campaign began. The School-to-Prison Pipeline, an ensemble of policies and practices that push students out of school and into contact with the criminal justice system, has been amply theorized by both scholars and survivors for decades. As Police-Free Schools Winnipeg described it, “many minor incidents in schools that would not otherwise result in a police report or criminal charges are escalated by police involvement. School Resource Officers (SROs) only force youth into contact with the law, and actively discourage students from overpoliced communities from attendance and participation in school activities.”

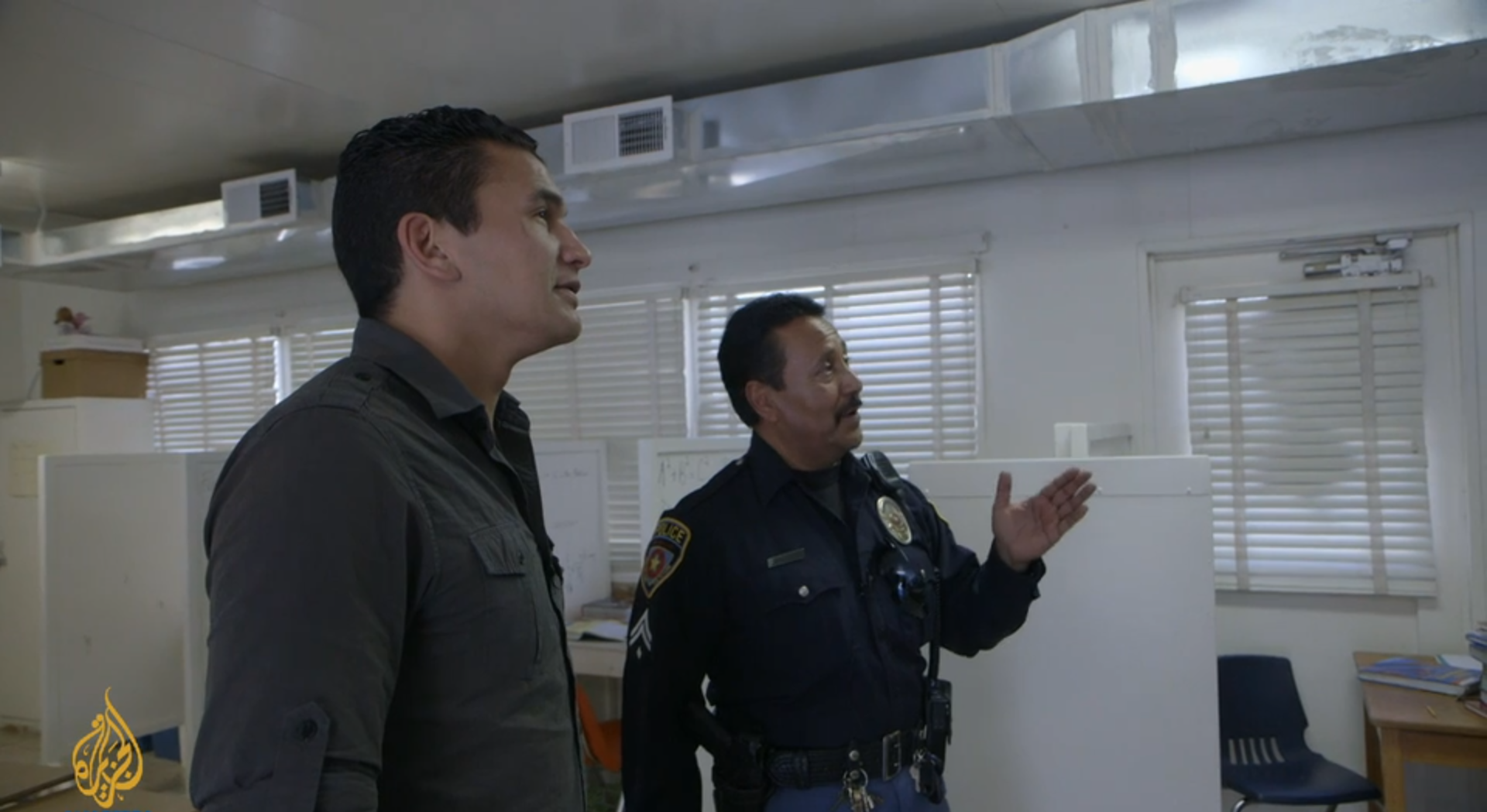

This pattern was observed by Wab Kinew himself shortly before his turn at party politics, in a 2014 documentary produced for Al-Jazeera’s "Fault Lines" series. In this feature, Kinew travels to Texas to interview teachers, students, and law enforcement on the negative impacts of police in schools. “With every horrific school shooting in the US, there are calls for more police officers in schools,” Kinew narrates. “But more police means students are more likely to be written up for misbehaviour, and eventually end up in prison.”

Kinew hardly flinches before the inevitable conclusion of his report—that first and foremost, police function to remove and to repel students from school rather than to support them, and that as police presence in schools increases, more and more teachers and principals rely upon SROs for everyday discipline. “One thing we heard as a criticism,” Kinew says, “is well, they’re cops. You put a cop in school and they’re going to start policing. All of a sudden they’re going to start ticketing things or they’re going to start enforcing laws in a way that wouldn’t normally happen, so you have a higher likelihood that the young people in the school are going to be criminalized.”

The harmful reality of the School-to-Prison Pipeline (sometimes ‘nexus’) was well-evidenced at the time of Kinew’s investigation in 2014, and these criticisms were already as old as the programs themselves. Even so, these initiatives continued to expand across the continent, with Canadian school boards and administrators persisting in the defense that this is a distinctly US problem; or failing that, a Toronto problem; or an inner city problem; but never a structural fact, let alone a designed outcome, of any program that grants law enforcement direct access to and power over youth.

Policing under review

Where there is abuse of power, there is resistance, and Police-Free Schools Winnipeg was only one of many campaigns across Canada to successfully remove law enforcement from education. In 2017, the Toronto District School Board voted to end its School Resource Officer program, one of the first in the country. In 2020, the Hamilton-Wentworth District School Board reluctantly voted to end its police liaison program after powerful student advocacy. In 2021, the Vancouver School Board voted to end its School Liaison Officer program and remove uniformed police from Vancouver schools.

In Winnipeg, Louis Riel School Division (LRSD) ended their School Resource Officer Program in 2021 after an independent, equity-based review of the program by researcher Fadi Ennab declared in no uncertain terms that SRO programs maintain systemic racism. “Most interviewed participants in this review expressed concern that the SRO program in LRSD disproportionately targets BIPOC families,” the report states, and the oral accounts therein closely correspond to those collected by the grassroots campaign. To date, the document has only been made publicly available in a heavily redacted version, as per the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act. Although its findings led the board to take swift action against the program, they have been equally careful not to publicize the full extent of its abuse.

WSD was the pilot project for police in Winnipeg schools, beginning in 2002 at the initiation of administrators. WSD is the largest in the city, encompassing 79 schools in the downtown and North End. This includes many of the city’s poorest postal codes, as well as many schools with majority Indigenous student populations and significant numbers of newcomers. According to demographic data collected by the division in 2021, the percentage of self-declared Indigenous students was equal to or greater than 50% in twelve elementary and nine secondary schools. At Niji Mahkwa Elementary and Children of the Earth High School, for example, over ninety percent of the student population were Indigenous. Notably, the SRO program was initiated at Children of the Earth and St. John’s High Schools, where testimonies collected by Police-Free Schools Winnipeg accused SROs of hounding specific students and aggressively pushing for suspensions and expulsions.

One testimonial reads, “I was expelled at the suggestion of the resource officer after a serious incident that required mental health care, adult intervention and support,” continuing: “I was provided a criminal assessment, and was immediately removed from any resources the school division could have provided me and my family.” This is a textbook demonstration of the School-to-Prison Pipeline, where police officers escalate behavioural incidents into life-altering encounters with the law.

At the time of these abuses, there were nine SROs assigned to WSD at public expense. The division itself paid almost half a million dollars per year for the program, alongside a smaller sum from the provincial government and an unspecified, in-kind contribution from the WPS. What were they doing there in the first place? By the WPS’ own account, their SRO programs are not intended to directly police students. It is a community relations program first and foremost, by which the police attempt to launder their image amid vulnerable youth. That said, the moment that this outreach is threatened, police are first to claim that the absence of police from schools places students in danger from their peers.

Practically, SRO programs grant police a foothold in targeted communities, and the Police-Free Schools Winnipeg campaign collected multiple stories of SROs recognizing teens outside of school, only to taunt and follow them in their home neighbourhoods. In light of this profiling behaviour, it’s striking that in 2016, years before any social movement had amassed against the program, the WPS proposed to station an officer in every high school throughout WSD.

This overreach and surveillance continued for years, during which WSD only sought to defend and expand the program. A methodologically dubious report on SROs in WSD, collecting data from 2012-2014, reported that found that “students who reported feeling very safe inside their schools were most likely to report that having SROs in their schools makes them feel safer,” while those who experienced schools as already unsafe felt that SROs made little difference, or made things worse. This seeming redundancy is telling, for if policing actively discriminates against a minority of students, then the positive impressions of the unhindered majority tell us little about the risks associated with police presence.

The equity-lens of the LRSD report was intended to correct such deceptions, and a related 2022 report by Ennab, published by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, depicted the practice of policing in North End and downtown schools in starkly different language than the 2014 survey. In addition to frequent accounts of discomfort around police owing to previous traumatic experiences, the report relates numerous incidents of police searches and arrests at school. “It is apparent that the involvement of school police officers turned situations of common misconduct into a criminal matter, causing harm to racialized students,” Ennab writes.

This closely resembles the conclusion that Mr. Kinew arrived at less than a decade prior while working for Al Jazeera. In the "Fault Lines" special, he reads from a similar report prepared for the U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights, noting that “the report found that minority students were far more likely to face disciplinary action or arrest. It also cited schools for widespread use of out of school suspensions, 95% of them for non-violent offences like disrespect and tardiness.” Unlike many of his peers in politics, Kinew cannot claim ignorance of the many issues with police in schools. We have it from his own mouth that “for many students, the journey to prison can begin at the start of the school day.” Needless to say, the practices that he condemned in 2014 haven’t changed; so who has he been speaking with in the interim?

Defunding and refunding the police

In 2021, WSD decided to end its SRO Program, but without any values-based commitment to keep children from police interference. Rather, the school board found themselves tasked with the approval of an austerity budget that forced difficult decisions. At the same time as the SRO program and the division’s annual contribution of over $449,000 came up for evaluation, so too did funding for occupational therapy, nutrition and milk subsidies, and other in-school supports. It was already ludicrous that the police were accepting money from an under-resourced public education system, where the yearly outlay on SROs could have supported the wages of ten Educational Assistants instead. But in 2021, a lean budget forced the matter to a crisis. The trustees’ decision to divest from policing did not acknowledge any of the local advocacy against the SRO program, nor the national context.

This strictly financial rationale has left the door open for police to reinsert themselves by way of classroom visits and special presentations, which are as frequently upsetting to students. From leering, stigmatizing presentations on internet safety or sexual health to fully armed storytimes, police officers continue to appear in WSD and LRSD schools under the pretense of community relations. In LRSD, where the SRO program was officially ended, a five-year-old boy was mauled by a police dog in 2022 during an officer’s visit; the boy required stitches to his lip and lost a tooth. During I Love to Read Month this February, police officers in WSD schools boasted of their lethal weapons, visibly displayed on their person, to captive audiences of nine and ten year olds.

These visits are solicited by school administrators, who remain susceptible to pressure from the WPS, and continue to rely upon police to fulfill roles for which they are entirely unequipped, from presentations on internet safety to routine storytimes. Even bracketing the stressful effects of police presence on marginalized students, or the use of these programs for community profiling by police, these are tasks for trauma-informed counsellors and trained experts. It’s straightforwardly neglectful to lean upon law enforcement for these services amid drastic shortfalls, but where the many harms of SROs are so well-documented, the open invitation is clearly ideologically motivated.

It’s not only administrators who are eager to reinstate the program by the back door. Since the removal of SROs from WSD, powerful forces have attempted to defend the program. Walter Schroeder, a wealthy out-of-town benefactor of several WSD schools, initially offered to pay for the SRO program himself. After this undemocratic proposal to effectively buy policy was rejected, it was revealed that Schroeder was also bankrolling the campaigns of candidates for school trustees who wished to run against the present board.

The board’s decision to defund the program on strictly financial grounds leave an opening for this kind of meddling, and we can readily see the connection between police penetration of schools and the forces of privatization in this susceptibility to outside funders. Since the program was removed, parents from Schroeder-backed schools have attempted to stack speaker lists at school board meetings, repeating vague demands to restore the program on grounds of safety concerns. Unlike the stories collected by the Police-Free Schools campaign and those reflected in the reports prepared for LRSD and CCPA, these appeals were not based on first-hand experience but issued from a place of moral panic and concern for “safety.”

The counter-movement to police-free schools is well-funded and enjoys strong political backing, from the NDP in particular. In Manitoba, Wab Kinew is leading the charge on behalf of the WPS, but earlier this year, British Columbia’s NDP government fired the entire Greater Victoria School Board, claiming that their 2022 decision to end the District’s School Liaison Officer program endangered students’ safety.

Yet the Greater Victoria school board had voted to end the program on the recommendation of the province’s Human Rights Commissioner, Kasari Govender, based on the findings of a 2021 report for BC’s Office of the Human Rights Commissioner. “Out of respect for the rights of our students, I strongly recommend that all school districts end the use of SLOs until the impact of these programs can be established empirically,” Govender wrote. “For school boards who choose not to take this step, it is incumbent on you to produce independent evidence of a need for SLOs that cannot be met through civilian alternatives and to explain the actions you are taking to address the concerns raised by Indigenous, Black and other marginalized communities.”

What’s next?

Wab Kinew and the Manitoba NDP have become the local face of this nation-wide backlash against Police-Free Schools as a human right, recently seizing upon a violent attack on a high-school student in order to justify their longer agenda. The incident, in which a 16-year old student at Neelin High School in Brandon was attacked with a sword, is unquestionably nightmarish. (The attacker was subdued by the police with a taser, and both he and the victim are recovering from their injuries.) Kinew and others have taken this eruptive violence as a clear sign that SROs must be reinstated in WSD as well, noting that the eventual police response to the attack in Brandon began with a student’s tip-off to their school’s SRO.

Plainly, and without instrumentalizing the attack for argument’s sake, this painful saga doesn’t demonstrate as Kinew and a chorus of right-wing commentators wish. Firstly, police do not and cannot prevent random or even pre-meditated violence. In the words of Christopher Schneider, a Brandon-based sociologist and expert on policing and social media, “a proactive strategy to prevent such incidents from happening is to increase school psychologists and counsellors in Manitoba’s high schools who could better recognize early mental health concerns and render the appropriate interventions, thus thwarting escalations in violence before they occur.” At best, policing is strictly responsive, and at its more typical worst, pre-emptively creates the conditions and profiles corresponding to desperate acts and their criminalization—and not necessarily in that order.

In the recent incident at Neelin High, the SRO who was alerted to the presence of a weapon in the school was not even in the building at the time. Wab Kinew and Brandon Police Service Chief Tyler Bates have spoken of a “decisive” and “seamless” response involving the SRO, but by all accounts the officer in question was working at police headquarters at the time of the call, and school staff had dialed 911 and moved into lockdown in the meantime. Clearly, in the event that a police response is required, schools access emergency services through the same channels as everyone else. Nothing in this situation suggests that a resource officer in the hall would have functioned preventively, or even hastened the response time of police. In fact, since SROs clearly remain at Neelin High, the more rational conclusion would suggest that their visible presence has done nothing to deter violent outbursts.

Amid sensational coverage of this attack, right-wing and pro-police pundits argue for increased surveillance and securitization of schools, pitting lurid anecdotes against a wealth of evidence-based research on the harms wrought by all such programs. This opportunism is to be expected, and as many of these pro-police voices align with the forces of privatization, it’s important to remember that the decision of select school boards to financially abandon rather than holistically reverse their SRO programs was always destined to produce this backlash. The LRSD report, for example, not only recommended defunding the SRO program, but reinvesting in robust social supports for equity-seeking groups. The CCPA report concerning WSD recommended a spate of “preventative and pro-active community-based solutions” over police infiltration of schools. Where have any such policies taken root, let alone with ample resources?

The events of last week clearly recommend early intervention in mental health crises over the ability of police to pre-empt violence. As urgently, the United Nigerians in Brandon Association has rallied in the aftermath of the attack to call attention to a crisis of racism in Brandon schools. In a recent Brandon School Division board meeting, parents requested more cultural spaces and anti-oppression training for staff within schools—proactive measures against racism that require no exacerbating police presence. These are tangible ways to keep students safe, but they defy the logic of policing at its basis.

The question remains: why is the Premier of Manitoba using this shocking incident to intervene against the decisions of an elected school board in another division altogether? This obviously slights local democracy and the ability of municipal bodies to make their own policies alongside the communities that they represent. As disturbingly, it’s confirmation that the NDP remains entirely beholden to the unelected municipal government of the police, to the extent that our Premier will veer widely out of his way to help the WPS in their years-long attempt to reverse and to contain the modest wins of local community against their bloating budget and lengthy record of violence.

Many of us recall how Wab Kinew and much of his present cabinet used local movements against police brutality to brazenly campaign against their opposition throughout 2020, advancing their own careers without saying a word against police killings as such. We recall how many of these apparently progressive politicians sought a mandate from the grassroots and professed to share movement concerns, until the moment they were able to do something about it. For those of us who remember, the silence of these politicians has been clear enough. But Premier Kinew’s vocal support for the police agenda in Winnipeg schools should be heard and named for what it is—a right-wing and politically motivated attack on the basic premises of anti-racist, equitable and accessible public education. Worse still, he knows the research that he flouts and has repeated these same talking points himself in a past life.

Premier Kinew’s call for armed cops in schools is unsurprising, and unopposed, the present NDP would certainly fund this harmful practice to the fullest extent. But as Kinew attempts to override the democratic decisions of elected school boards, not to mention the concerns of parents and students, we need to pay renewed attention to the health and popular attendance of these spaces. So long as people like Walter Schroeder attempt to buy elections and to reinstate police in schools as a private security, and police continue to implore compliant administrators for more access to students, the wins of 2021 must be vigorously defended. In this respect, Kinew’s pro-cop NDP are only the political arm of a comprehensive strategy. As we seek to expand our defense of vulnerable students and their families, and of unhindered access to public education as a human right, we’re going to face powerful propaganda from all of the forces above—but Kinew’s offensive only speaks to the extent of our unfinished work, and to the power of the movement precedent behind us.