No, they don't – and here are five reasons to oppose them

After a decade-plus of talking about the idea, it’s becoming increasingly likely that Winnipeg will equip its police force with “body-worn cameras” (BWCs) — body cameras, for short — in the foreseeable future. Winnipeg Police Board chair Markus Chambers is a vocal proponent of the technology, stating in early 2023 that body cams are “not a matter of if, it's a matter of when.” Chambers reiterated support for the idea a year later, following the WPS killings of three people in a month. Most recently, he again issued support for body cameras in the wake of the police killing of Jordan Charlie at Unicity shopping centre; the RCMP has also started to rollout the technology in Manitoba.

The case for body cameras is largely understandable: the theory goes that if police violence is fully captured on video, it should be clear what happened in an encounter with police and investigators won’t have to rely on anyone’s words or eyewitness accounts alone. Some also believe that body cameras — along with strict regulations governing their use and disclosure of footage — will deter police violence and improve relations between the cops and civilians. Given the horrific treatment of mostly Indigenous and racialized families fighting for answers from bureaucratic and pro-police institutions like the “Independent Investigation Unit” and public inquest processes, body cameras are perceived as at least part of a solution that can prevent such atrocities from reoccurring.

Unfortunately, extensive research from across North America — including excellent work by Brandon University’s Christopher J. Schneider — suggests that we need to be much more skeptical of the promise of body cameras. Notably, Axon, a publicly traded corporation and the largest producer of body cameras, invented the Taser, which it also falsely sells as a technological solution to police violence. Wrongfully perceived as a solution to police violence and a mechanism for accountability, the truth is that body cams cause lots of harm and do little good. Police forces that have already implemented body cams continue to harm and kill. This piece summarizes five of the main concerns about body cameras, and calls for the public to reject body cameras and refocus on the defunding and abolition of the police.

1. Body cameras don’t reduce police violence

One of the central claims in favour of body cameras is that equipping cops with the technology will reduce police use of force and civilian complaints as a result. However, extensive research shows that the evidence for this claim is extremely flimsy. A 2021 review of body cameras for the Canadian Criminal Justice Association (CCJA) summarized it this way:

“Available research suggests that the technology may not provide the benefits that were initially expected.”

For starters, the studies that have suggested dramatic improvements in these areas are highly questionable. A landmark experiment that’s since attained near-mythical status happened in the city of Rialto, California, in 2012–13. Serving as the “first peer-reviewed controlled experiment on the effect of BWCs on the use of force by police,” the Rialto study produced seemingly incredible results, including a huge reduction in use-of-force incidents and civilian complaints.

However, the Rialto study only involved 54 cops — a sample size far too small to compare to larger forces, such as the WPS, which employs more than 1,350 officers. Besides this, Rialto’s local police chief was a graduate student researcher directly involved in the experiment’s design and operation. Brandon University professor Christopher Schneider explained that “there have been numerous replication studies that have followed [Rialto] and some of these have found no statistical significance [of reduced use-of-force incidents and complaints against police] between officers wearing cameras and without cameras.”

A major study that undermined the Rialto experiment and others like it was conducted in Washington, DC, between mid-2015 and late 2017. Involving more than 2,200 officers and producing five times the video footage as the Rialto trial, the study found that body cameras “had no statistically significant effects on any of the measured outcomes.” An expert interviewed by the New York Times about the findings called it “the most important empirical study on the impact of police body-worn cameras to date” and that “the results call into question whether police departments should be adopting body-worn cameras, given their high cost.”

These findings have only been further supported in recent years with a series of meta-studies — studies of studies — finding that “BWCs have not had statistically significant or consistent effects on most measures of officer and citizen behavior or citizens’ views of police” and that “despite their widespread and growing adoption, the current evidence regarding the effectiveness of body-worn cameras is mixed.”

2. Body cameras will further expand police surveillance and prosecutory powers

While body cameras are often demanded by the public as a way of improving police oversight, the technology has instead long been discussed by politicians and police forces as a key means of bolstering surveillance and evidence collection, ultimately protecting police.

For instance, a 2018 report by the US Bureau of Justice Statistics found that the primary reasons that local police and sheriffs’ officers had acquired body cameras were to “improve officer safety, increase evidence quality, reduce civilian complaints, and reduce agency liability.”

Winnipeg’s own police board and city council have frequently discussed similar motivations, as well. A motion introduced by police board chair Scott Fielding at a 2013 police board meeting that called on the WPS to study body cameras argued that “police agencies using body-worn cameras have reported that this technology has many benefits to both the public and police officers, such as high-quality evidence to support prosecutions and protection for officers from false allegations of misconduct” (it also cited the aforementioned Rialto study as evidence of its supposed effectiveness).

In a council meeting a few weeks later, the primary reason that Fielding gave for the technology’s use was for “instances where people are making false allegations against police officers,” along with providing “quality evidence to use in prosecutions.”

Similarly, a budget referral made by the Winnipeg Police Board in mid-2021 that would have resulted in massive spending on body cameras noted that “early indications show BWCs improve evidence collection and documentation and provide efficiencies to criminal prosecution” (this attempt was voted down by council, in part due to community pressure).

This stated objective of further increasing surveillance and prosecutory powers is extremely concerning given the ongoing escalation of cops against their critics. Body cameras essentially equip every cop with a moving CCTV camera, including possible facial recognition using artificial intelligence that can be weaponized in many settings – including protests against police violence. There’s absolutely no reason to trust police with existing surveillance powers, let alone massively expanded capacities through technology like body cameras.

3. Body camera footage can be extremely difficult to obtain by the public — especially in Canada

A common and very reasonable concern about body cameras is the ability for cops to turn off or tamper with them to minimize accountability. There are many examples of this happening around the world. Most body camera regulations carve out exceptions to their activation, such as footage involving children and youth or situations in which “a victim or witness is reluctant to cooperate when the BWC is recording, or requests that officers do not record in a sensitive situation.” Cops exercise extreme discretion in all of their activities, so the possibility of body cameras being turned off – or even the cop turning away or otherwise obstructing filming – is certainly a concerning one.

With that said — and with obvious caveats like the willingness of cops to ignore or abuse the rules whenever they like — there have been fairly significant consequences for police caught doing this, ranging from prosecutions collapsing to cops getting arrested and charged for destroying or tampering with evidence, including an FBI investigation into the trend. Some states have even contemplated introducing felony charges against cops who turn off body cameras.

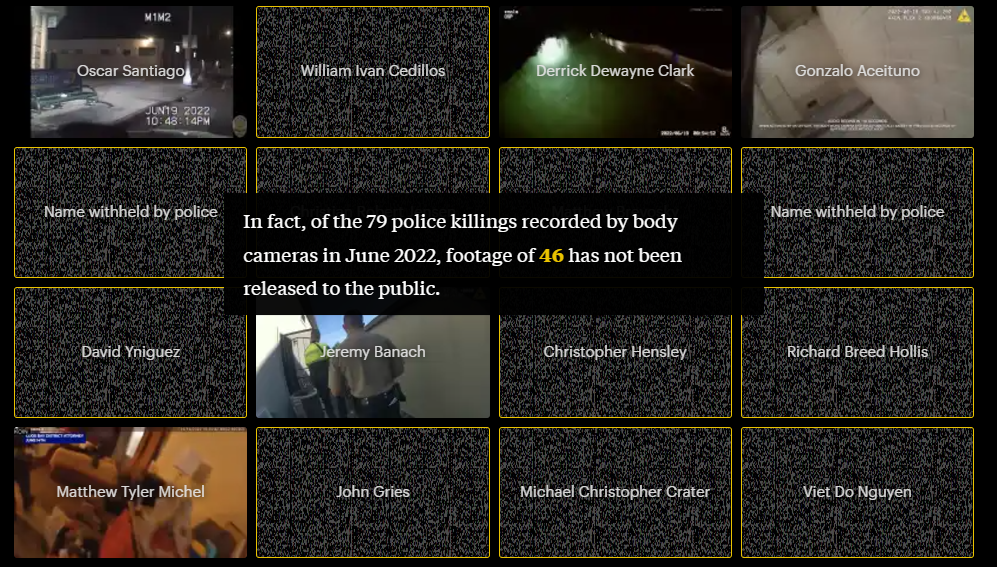

At this stage, the bigger concern appears to be the difficulty for civilians to actually access body camera footage outside of court settings. In the US, “departments across the country have routinely delayed releasing footage, released only partial or redacted video or refused to release it at all.” And the situation is even worse in Canada. As Schneider has explained, “police, because of privacy restrictions and legislation in the Canadian context, are less transparent with body-worn cameras than their American counterparts.”

A Globe and Mail article from early 2023 detailed these byzantine dynamics. When a lawyer filed a freedom of information request for body camera footage of police violence to the Toronto Police on behalf of a client, the police initially refused to release the video because it “currently related to a labour matter in which our institution has an interest.” The classification of footage as part of an “active investigation” can also allow a police force to deny access. This process becomes even more difficult for someone who isn’t directly implicated in body camera evidence, like a journalist, because many parts of a released video can be redacted and altered by disclosure specialists on the grounds of privacy.

University of Toronto criminologist Scot Wortley told the Globe and Mail:

“There seems to be a definite pro-police policy with respect to when this information can be released. It’s released strategically, when it supports police interests. But if it makes the police look bad, then that video footage is going to be held back.”

The lawyer involved in the conflict with the Toronto Police agreed:

“I think that where body-camera footage is going to damage the reputation of the police, they will fight it at all costs. They have unlimited resources to do so.”

Many are understandable optimistic that body cameras will improve transparency and require cops to demonstrate what actually happened during high-profile instances of police violence. But even if police forces are occasionally pressured into releasing footage, or required by law to disclose it during court cases, the vast majority of video evidence will likely never see the light of day.

4. Body cameras are extremely expensive and divert resources from actual safety responses

Something frequently and conveniently left out of the body camera discussion is that they’re extremely expensive. Firstly, there’s the upfront capital costs of purchasing the many hundreds of cameras. Then there’s the ongoing price of data storage, software, and other supports. Finally, there’s the huge increase in salaries, benefits, and pensions for the newly hired police employees tasked with running the body camera program, largely involved in disclosure and freedom of information duties. Almost all of this likely represents additional funding to police.

The aforementioned budget referral by the Winnipeg Police Board in mid-2021 laid this out in great detail. The capital costs for the body camera program — just the cameras and related hardware — was estimated at a whopping $32.1 million over six years, including $6.8 million in its first year (these costs are almost certainly higher now than they were in 2021, too).

While this document indicated that years two through six of the capital costs would be funded by transfers from the police force’s operating budget, it seems extremely unlikely that the WPS would accept loss of between $4.8 million and $5.5 million every year from their operations; particularly given the new provincial government’s willingness to increase police funding, it seems far more probable that they and the city would agree to increasing their share of the WPS budget accordingly.

The WPS has also long refused to fully implement supposedly mandated “expenditure reductions” targets, consistently blowing past their budgeted funds and requiring council to cough up even more public money; the latest budget projections anticipate the force missing this year’s target by $4.3 million.

Further, the $32.1 million in capital costs doesn’t include the increased staffing costs. In total, it was projected in the budget referral document that an additional 16 full-time positions would be required for the program; even if some of these positions are reallocations of existing personnel, this would represent an additional $1.7 million to $2 million per year, over and above the capital costs. This means that if 2021 financial estimations were accurate — and they are likely higher by now — the WPS will be spending an additional $6.5 million to $8.5 million on the body camera program every single year.

Axon, the body camera manufacturer, has claimed that the technology will result in downstream cost-savings due to greater efficiencies in evidence collection and court proceedings. However, as noted in the 2021 CCJA report, “most of these claims have come from manufacturers who have a significant stake in selling their products.” At no point should it be forgotten that Axon is a capitalist enterprise vying for profit, and has no actual interest in actual safety responses that would reduce the case for their highly expensive and state-funded products.

5. Body cameras don’t guarantee justice, even if everything “works”

But even if body cameras work as advertised — that they’re turned on when they’re supposed to be, that they produce high-quality footage and audio, and that the videos are released in a timely manner — there’s no guarantee that will result in justice or change.

Simply put, body camera footage is not an objective record, but based on subjective interpretation. For instance:

“When TheGrio news network recently sent footage of the same police use-of-force incidents to 10 experts, interpretations of what they saw and heard varied dramatically, even on basic matters including whether or not the subject complied with officer demands.”

Similarly, the visual perspective of the body camera itself shapes interpretation. Schneider and Erick Laming recently explained: “When police are otherwise videotaped — with a dash camera for example — they can be seen in the frame. But that’s not the case for BWC footage. Therefore, evidence suggests, people who view BWC video of an incident when compared with a dash camera recording of the same incident are less likely to assign blame to a police officer.”

Countless police killings and assaults have been filmed but have not resulted in charges, convictions, or other forms of discipline against officers. In Manitoba, “subject officers” involved in causing deaths and serious injuries are not required to cooperate with “independent” investigators like the IIU, and even if the IIU does think there’s merit to pursuing charges, the Crown overwhelmingly rejects that course of action. In the US, where body cameras are more common, it’s been found that police forces “have frequently failed to discipline or fire officers when body cameras document abuse and have kept footage from the agencies charged with investigating police misconduct.”

More generally, Section 25 of the Criminal Code protects any use of force if the cop “believes on reasonable grounds that the force is necessary for the purpose of protecting the peace officer, the person lawfully assisting the peace officer or any other person from imminent or future death or grievous bodily harm.” This clause is often invoked by the Crown to explain why cops don’t get charged.

Additionally, cops and their lawyers will frequently appeal to the abusive and victim-blaming continuum of force — which claims that police use of force is proportional to the person’s resistance and that excessive use of force could be avoided by the individual not resisting police intervention — and the debunked diagnosis of “excited delirium” that allows police to diagnose a “medical” cause of death in situations where the only other plausible cause of death would be murder. Alleged drug use is also a constant excuse for police violence, including the spectre of supposed meth-induced superhuman strength necessitating use of restraints that have often led to death.

Ultimately, the crisis of police violence is not due to any lack of video footage but the institution of policing itself. The only way to end these killings and honour those who have been killed and harmed by police is for our communities and organizations to recommit to defunding and abolishing the police and replacing the harmful institutionwith alternatives that create true safety and are genuinely accountable to the community. Body cameras only further entrench police power and funding, and should be rejected as part of a broader struggle against the violence of policing.