Afolabi Stephen Opaso was a 19-year-old Nigerian international student at the University of Manitoba (UM). Afolabi lived at 77 University Crescent, a neighbourhood close to campus that is known to be home to many international students. Afolabi’s friend described him as a great person to be around and someone who loved dancing and hip-hop music. On New Year’s Eve, the cops were called for help because Afolabi was in distress. The WPS officers who arrived on scene shot Afolabi three times in his apartment, killing him. While the WPS were swift in stating that Afolabi’s death was not related to racism, they also described him as “erratic” and “armed with two knives.”

According to Afolabi’s family lawyer, this was the second time Afolabi experienced a mental health crisis; his first was last July. The WPS revealed they did have an “encounter” with him last July, where they “assisted him by providing him with a ride." As can clearly be seen, sending violence workers to respond and give “rides” to Black students in crisis who need care and support is not just inappropriate, it’s lethal.

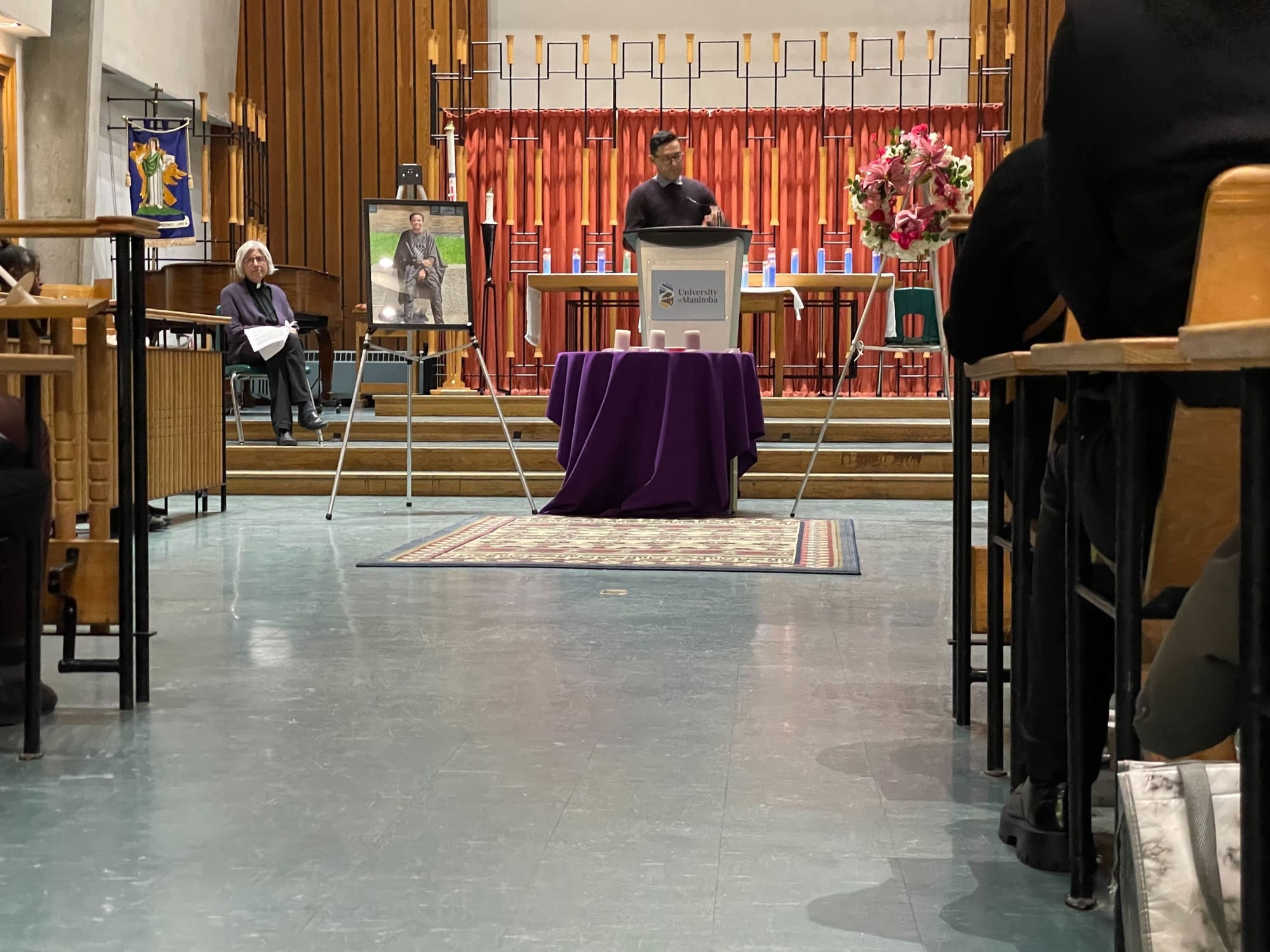

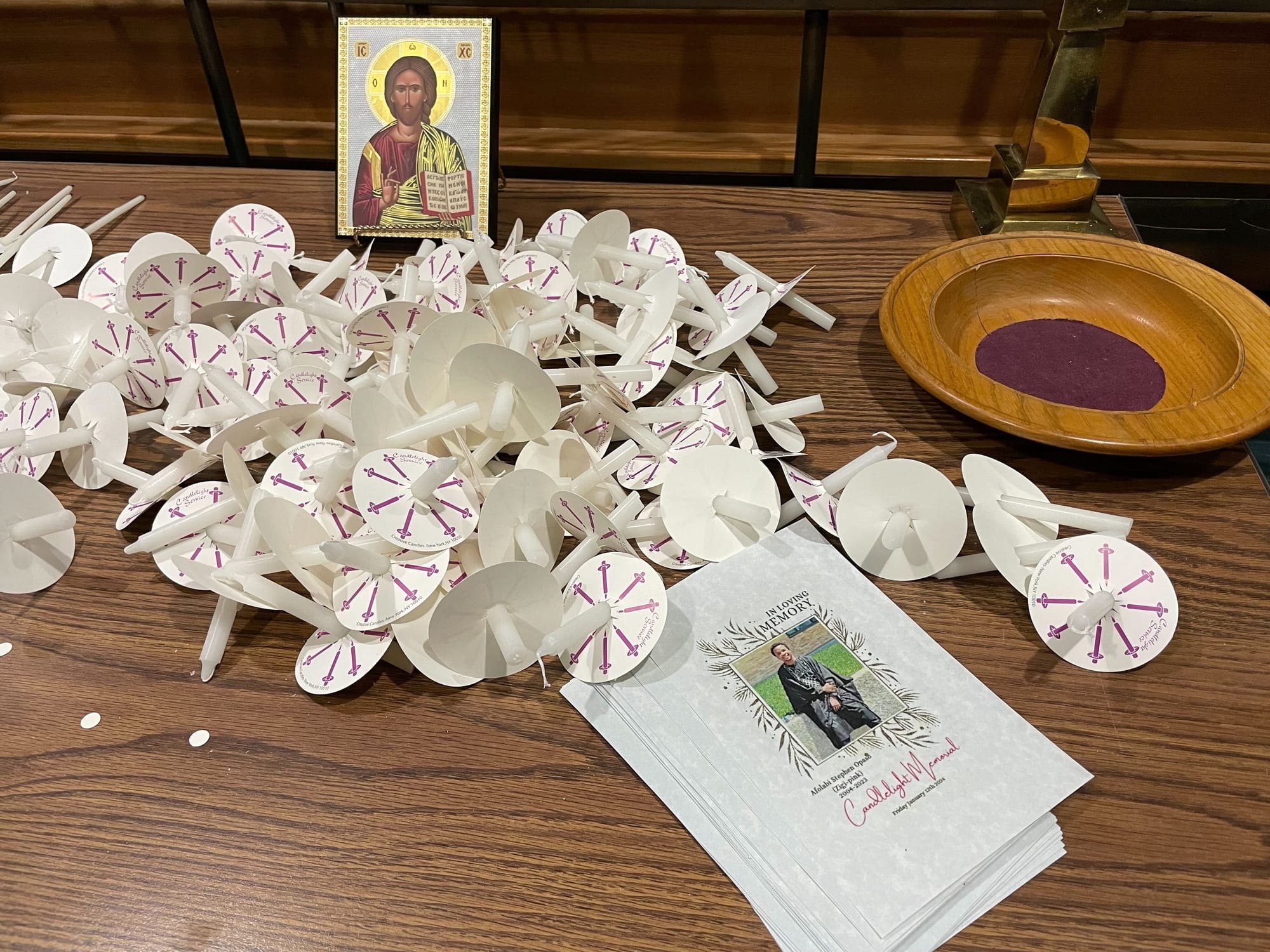

After hearing the news of Afolabi’s death, the Senior Special Assistant to the President of Nigeria on Student Engagement condemned the WPS’ “barbaric” and “racially motivated” killing of Afolabi and threatened to close the Canadian embassy if there was no justice. An online petition demanding justice for Afolabi has almost 10,000 signatures, with the text writing that “this incident has left a deep scar in our hearts and raised serious concerns about police brutality and racial profiling.” According to the University of Manitoba Nigerian Student Association, Afolabi’s death has “ignited pain, fear, and frustration within our community, prompting us to demand answers. Mental health should never be a death sentence.” Friends of Afolabi, at his vigil, said that he struggled under the pressures of being far from home and with finding affordable housing, and was working two jobs to try pay the bills.

I am a former international student and also someone who once managed community mental health and social supports that excluded international students. I am also someone who has evaluated the police in an educational setting. Through these compounded experiences, I understand these deaths as occurring at a nexus of migration, education, policing, and mental health.

Maddening social contexts for international students

Like Afolabi, I arrived in so-called “Canada” as an 18-year-old international student. Leaving family and living away from home is difficult for many students at the best of times. All your achievements and successes here become a reminder of losses there. Many international students grew up surrounded by “eyes that light up,” as Toni Morrison would say. Here, many students encounter white settlers whose eyes are fearful or indifferent. Without one’s source of meaning and nourishment, it is difficult to adapt to flux and movements across borders.

Most international students are from colonized regions in the Global South, and their families often depend on them. So, if your country is on fire or your parents encounter a crisis, you can be tormented by unbearable feelings of shame and survivor’s guilt. This can result in post-traumatic stress, which causes some international students to regress “to a primary state of unintegration where the self is at the mercy of psychotic anxieties and the student is at risk of suicide.” Anti-Black racism and policing can compound these existing stressors on international students.

Black international students live in so-called “Canada” under maddening social contexts, to borrow from critical Black scholar Dr. Idil Abdillahi, in which they must navigate stressors such as racism and discrimination, isolation, processes of acculturation, language difficulties, ableism, and academic pressure. With these structural conditions in mind, it becomes clear that Afolabi’s death did not happen singularly or by accident. To borrow again from Dr. Abdillahi, “the mad Black person without property is the perfect antithesis of this violent brutal capitalist society — they must be made to disappear by all means necessary.”

It is important to situate the experiences of international students within the context of anti-Black racism because it can provide answers to questions that governments and institutions (such as the police and the university) will evade, if not actively sweep under the rug.

To date, the UM administration has acknowledged Afolabi by 1) stating that they will lower its flag and 2) sending a mass email to UM students stating that Afolabi’s death is “tragic and sad.” So far, the UM administration has not mentioned its commitment to addressing anti-Black racism, a commitment it made by signing the Scarborough Charter on anti-Black racism and Black Inclusion in 2022. The UM administration has treated Afolabi’s death as if it occurred naturally—and only requires sympathy—instead of condemning it for what it truly was: the culmination of systemic racism and ableism carried out by the WPS as agents of the state. How serious is the University of Manitoba about tackling anti-Black racism?

International student permit and precarious migration

In 2002, I lived in the United Arab Emirates. I visited an office called “Canadian Management Consultants,” where my parents were charged 5,000 dirhams (around CAD$2,000) to apply for a study permit and a university application for me. Both of these services should only cost a few hundred (not thousand) dollars. I applied to the University of Manitoba because according to the recruiter who I met at an education fair that same year, it is a place for success in a city that can be "cold" but with potential.

Only after arriving in Canada do many international students realize that they are getting scammed—and it’s only getting started.

When I arrived in Canada, international students were not allowed to work off campus, which forced us to do minimum wage jobs. My first job was cleaning dishes, which became my entry into racialized labour on campus. Brown students like me would load the dishwasher, Black Nigerian students would scrub pots, and white managers would supervise us.

I became friends with Nigerian students, some of whom lived in the same building where Afolabi would eventually live and be killed by police. That building was seen as the “best of both worlds”: walking distance to campus and cheaper than living directly on campus. Students are often told living close to campus is “safer” than downtown, yet white supremacy is not confined to the downtown area. For example, several years into my program, I was physically assaulted on campus by a group of white students.

Today, an international student is allowed to study in Canada on a “student permit” if they can prove that they have access to more than $20,000. Unlike a refugee or an immigrant who is granted “permanent residency” with a path to citizenship, a student permit implies that students are only expected to be in Canada temporarily to study. International students are authorized to live in Canada, but are not usually allowed to work more than 20 hours off campus (there is currently a short-term exemption until April). In 2017 an international student was arrested and later deported for working too many hours, just days before his graduation.

International students are also not entitled to access publicly funded services. In 2018, the Manitoba PCs cut healthcare coverage for international students to save $3.1 million, and international students have since faced six-figure bills for healthcare costs. This means that many international students have to pay four times the tuition fee a local student pays, and yet they receive insurance that barely covers three counselling sessions (assuming they know about it). Additionally, even if someone like Afolabi was eligible for health coverage like a citizen, racism is rampant in healthcare.

Thus, many international students can find themselves with a “precarious migrant status”: on top of being excluded from the privileges and benefits of Canadian residency or citizenship, an international student’s existence in Canada is conditional on meeting the stringent requirements of their student permit and educational programs (Bunjun 2021, 164). Failing in university means that students risk losing their study permits and their rights to stay legally in Canada. So, for an international student, “when illness strikes or an accident happens, the entire previous equilibrium collapses” (Sayad 2004, 180). If a student is in crisis and cannot meet their program requirements, they can become at risk of deportation, which further worsens their situation. Even if one restores their health, it may be difficult to restore an immigration status once you lose it or do not meet the requirements.

For this reason, many international students and others with temporary residency status do not seek help—even when desperate—because this “help” may disrupt their education or get them deported from Canada. Afolabi evidently needed attention and care, given his encounter with police and hospital months before he was killed. A visit to the hospital is not going to “fix” a mental health crisis, and Afolabi’s police encounter could have made him feel worse, like many Black youth experiencing a crisis.

Studying unsupported during multiple crises

The ongoing COVID pandemic continues to highlight how Black and marginalized communities that are structurally disadvantaged by multiple harms (i.e, social, economic, and emotional harms) feel a “suffocating, all-encompassing, and relentless” pressure. Various scholars and advocates have spoken about the difficulties facing international students, including racism, skyrocketing cost of living, and difficulties finding employment and affordable housing. They also criticize educational institutions for recruiting increasing numbers of international students without offering adequate support to those already recruited.

In 2018, I was responsible for managing the Community Wellness Programs at Mount Carmel Clinic. One of the programs was funded by Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) to support newcomer immigrants and refugees who had a permanent residency card. This meant that international students were ineligible for services. I once received a call from the University of Manitoba asking about a possible referral option for an international student dealing with trauma and grief. Even if eligibility was not an issue, the available counselling supports funded by Universities and the federal government are intended to support individuals in coping with short-term stress and not immigration processes or systemic racism.

This is the pattern: Black international students get punished for trying to seek help. In 2020, Ella—a 22-year-old Nigerian student at the University of Manitoba, just like Afolabi—experienced a mental health crisis. She didn’t have prior mental health problems (just like what Afolabi’s parents said about him), but after almost a year of COVID lockdowns, isolation, and disrupted classes she felt depressed and suicidal. After calling the Winnipeg police, Ella was hospitalized for nine days, some of this time under a forced “involuntary psychiatric” hold. Upon her release, she had to deal with an astronomical bill of $38,311, not covered by her insurance because she was not taking as many courses as required. Then, the Canada Border Services Agency investigated her student permit because they are mandated to deport non-residents who have not paid large medical bills. Notably, Afolabi’s family is currently fundraising for $40,000, an amount similar to Ella’s bill, to cover the cost of the funeral and legal work.

According to a funeral home in Toronto, international students from India are dying of suicide at an alarming rate, with up to five to seven bodies repatriated per month. The federal government is aware that many international students under the age of 25 have died in recent years, but they are choosing to ignore this crisis. Unsurprisingly, international students have continually asked for more and better resources, especially since their study is estimated to bring more than $23 billion to the Canadian economy. However, the federal government insists that it is limited in its ability to respond and deflected the blame to the provinces.

While some international students commit suicide, others are getting lynched in public spaces in several other countries. According to a recent report, Nigerians abroad are being targeted and killed with impunity; 300 Nigerians, some of whom are international students, have been murdered extrajudicially outside of their country by non-state actors between the years 2016 and 2023. Unlike these Nigerian international students, however, Afolabi was shot and killed by police.

Anti-Black racism and policing

Black people are disproportionately targeted and impacted by police violence due to systemic racism. Canada has “a long and well-documented history of racism and abuse” to eliminate Indigenous resistance and ensure a settler colonial order built on land theft and slavery (Palmater et al. 2019, 26). In 2021, I was hired by the Louis Riel School Division to independently review the involvement of the WPS in their schools. The report noted that police involvement in schools results “in negative experiences causing harm to racialized students; this review documents several incidents of discrimination on the basis of race and gender.” I also documented experiences where police were weaponized against racialized students to intimidate and criminalize them.

The statement I quoted above, along with direct experiences of police harm, was redacted from the report that the school division publicly released almost two years later. Both this review and my community based research in the Winnipeg School Division recommended ending all police involvement in schools.

Police are violence workers who expose racialized and marginalized communities to danger. Most people I interviewed, including students and educators, did not want relationships with police. And yet, in spite of mounting evidence of police killings and racial profiling, police are increasing their involvement on university campuses through collaborating with and training “institutional safety officers.”

Afolabi, like many other Black people, was treated by police as a threat to be criminalized or eliminated. The audio recording capturing the last moments of Afolabi’s interaction with police show that they did not attempt to de-escalate Afolabi. As the senior official in Nigeria stated, “the police officers would have acted differently if [Afolabi] were to be a white [person].”

Afolabi’s death is reminiscent of the WPS killing of Machuar Madut, a South Sudanese man who was holding a hammer in his apartment in 2019. Among so many others, incidents like these echo the 2015 Toronto police killing of Andrew Loku, an African man holding a hammer in the entrance of his home. These deaths are far from coincidental. The disproportionate killings of Black bodies with mental illness or psychiatric disabilities shows that “living mad while Black” threatens the existing status quo that is based on white supremacy. As the case of Afolabi illustrates, when Blackness and mental health intersect, police kill with impunity.

Tackling anti-Black racism in university and beyond

Given that Black students already experience racism in educational spaces through the curriculum and their interactions with administrators, professors, and fellow students, involving the police in students’ lives compounds the racism they are already facing. Police involvement can result in criminalization and in turn, a “double punishment.” As such, when students get a criminal record, not only is their education impacted, but also their visa status, and their right to legally stay in Canada may be revoked. Thus, the ongoing double punishment of international students shows that anti-Black racism is institutionalized not just through the justice system but also the immigration system.

We can support demands for accountability and justice for Afolabi and all victims of police brutality. Since all students deserve better education and safer communities without policing now, we must abolish these systems and rebuild alternatives that are not based on a hierarchy of (non)citizenship and race. Reforming institutions such as the police or universities will not prevent the targeting and killings of racialized community members.

International students need appropriate education and supports that are explicitly anti-racist and empowering. Instead of treating international students as a commodity and a financial source to generate profit and harvest for “skills,” we need to consider their humanity and potential as future members of our global community. Many international students do want (or have no other choice but) to stay here. This can be easily done if international students are given permanent residency on arrival, along with full labour and social rights and being charged the same fees as citizens.

If Afolabi and his friends had access to cultural workers or mental health supports that humanize Black lives, instead of violence workers who are trained to kill, maybe he would still be breathing. The reality is that the “Canadian dream” is a nightmare for many racialized people with precarious migratory statuses who can find themselves killed by police in a storm of anti-Black racism.